-

iestinstrument

In situ Crystal Structure Growth and Control for Enhancing Cathodes Comprehensive Performance in Ultrahigh Nickel-Layered Lithium Cathodes

1. Abstract

Ultrahigh-nickel cathode s promise exceptionally high energy and power density, but scaling Ni content (x ≥ 0.9 in LiNixCoyMn1−x−yO2) brings crystal-chemical and kinetic challenges—Li/Ni disorder, anisotropic stress during deep delithiation, and surface instability at high voltage. Here we summarize a recent study that uses in-situ growth of tailored precursors and a multistage sintering/annealing strategy to produce an LiNi₀.₉₁Co₀.₀₄₅Mn₀.₀₄₅ material (G-Ni91) with fine primary particles, a gap-type secondary morphology and a ~2 nm surface rock-salt layer. These intrinsic structural modifications reduce Li/Ni antisite defects, accelerate Li-ion transport, lower charge-transfer resistance and markedly improve rate capability and cycle life versus a conventionally prepared counterpart (D-Ni91). Key metrics: first discharge 212.4 mAh·g⁻¹ (0.1C, 2.7–4.3 V); 159.0 mAh·g⁻¹ at 5C; 92.6% capacity retention after 100 cycles at 1C; diffusion coefficient ≈2.02×10⁻⁹ cm²·s⁻¹ (G-Ni91) versus ≈5.16×10⁻¹⁰ cm²·s⁻¹ (D-Ni91).

2. Research Background: The Challenge of Ultrahigh-Nickel Layered Cathodes

The rapid expansion of the new energy vehicle market has led to surging demand for lithium-ion power batteries. Diverse, large-scale applications require commercial batteries to possess high energy density, high power density, and low cost. Among various cathode materials, ultrahigh-nickel layered LiNixCoyMn1-x-yO2 (x ≥ 0.9) cathodes have become a key research focus for modern power batteries due to their higher energy density and superior rate capability. However, increasing the nickel content exacerbates Li⁺/Ni²⁺ cation mixing, hindering lithium-ion transport and leading to reduced specific capacity and rate performance. The two-dimensional ordered structure of these materials, with alternating lithium and transition metal layers, is prone to structural degradation and phase transitions during deep delithiation, accelerating side reactions and compromising long-term cycling stability. Furthermore, reducing cobalt content can trigger structural collapse at charging voltages ≥ 4.3 V, causing rapid capacity fade. While increasing material density is a common approach to enhance cycling stability and ensure tap density, it often restricts Li⁺ transport, harming capacity and rate capability. Current improvement strategies like element doping, surface coating, or core-shell structures modify but do not fundamentally alter the intrinsic material structure, offering limited electrochemical gains. This study aims to provide a new strategy for developing cathodes with both high energy density and long cycle life through intrinsic structural design and control, utilizing an innovative in-situ growth method.

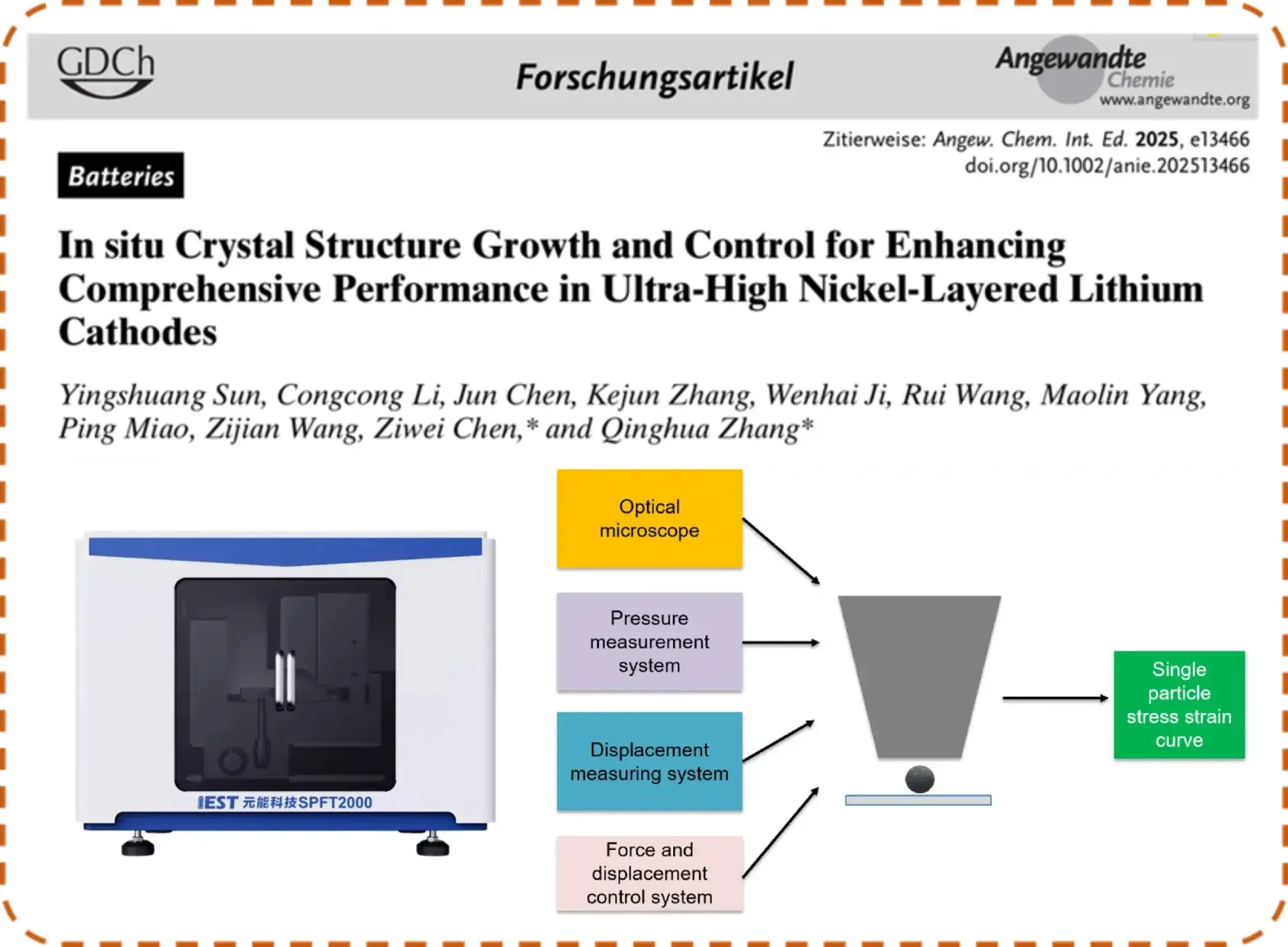

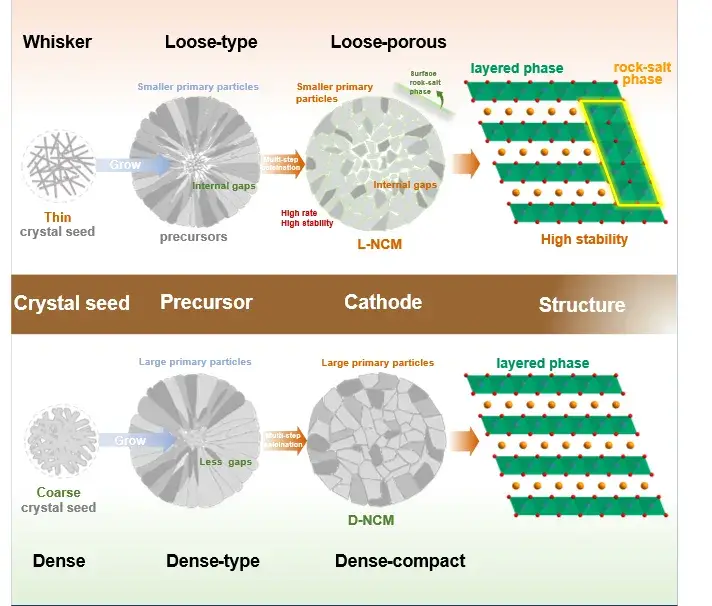

3. Work Summary: Novel Synthesis and Structure Design

Recently, the team of Qinghua Zhang and Ziwei Chen at Zhejiang University employed intrinsic structural design and an in-situ growth method using fine-whisker seeds. This innovative approach successfully prepared an ultrahigh-nickel precursor featuring fine primary particles and a secondary particle with a hollow core structure. Subsequently, they synthesized the ultrahigh-nickel cathode material LiNi0.91Co0.045Mn0.045O2 (termed G-Ni91) via a multi-stage sintering-annealing strategy. G-Ni91 possesses finer, more uniform primary particles and exhibits a unique interstitial-type internal structure. Notably, a rock-salt phase structure was also observed on the G-Ni91 surface. Electrochemical tests reveal that G-Ni91 delivers a first-cycle discharge capacity of 212.4 mAh g⁻¹ at 0.1C between 2.7-4.3 V, and demonstrates excellent rate capability with 159.0 mAh g⁻¹ at 5C. This is primarily attributed to its interstitial secondary structure and fine primary particles, which enhance lithium-ion transport kinetics. Regarding cycling stability, G-Ni91 maintains a high capacity retention of 92.6% after 100 cycles at 1C (2.7-4.3 V). It also shows excellent stability at 50°C, retaining 87.3% capacity after 100 cycles. This significant improvement stems from the synergistic protective effects of the uniformly distributed primary particles, interstitial secondary structure, and surface rock-salt phase. The related research was published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition under the title “In situ Crystal Structure Growth and Control for Enhancing Comprehensive Performance in Ultra-High Nickel-Layered Lithium Cathodes“.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram comparing the macroscopic and microscopic structural changes during the in-situ growth of different cathodes.

4. Key Findings: Structure, Electrochemistry, and Mechanism

4.1 In-Situ Growth, Structural Control, and Characterization

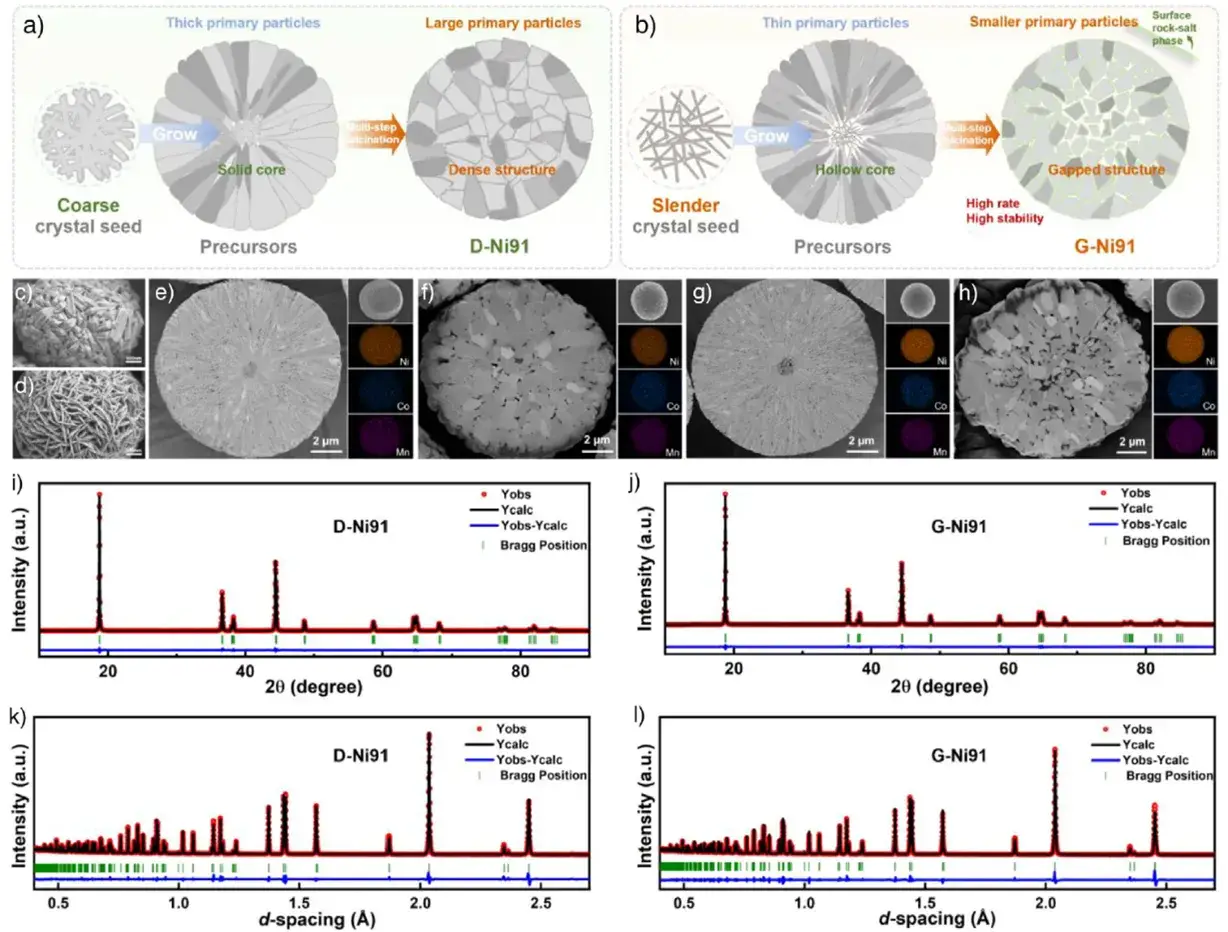

XRD and NPD Rietveld refinement confirm both the control (D-Ni91) and novel (G-Ni91) cathodes possess well-crystallized hexagonal α-NaFeO₂ structures. The higher I(003)/I(104) peak intensity ratio for G-Ni91 (2.108 vs. 1.976 for D-Ni91) indicates fewer Li⁺/Ni²⁺ antisite defects. NPD refinement further verifies a lower cation mixing ratio in G-Ni91 (0.208% vs. 0.227% in D-Ni91), which helps reduce the Li⁺ diffusion barrier, improve kinetics, and enhance reversible capacity, initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE), and high-rate performance. Morphologically, while both secondary particles are spherical (~13-14 μm), G-Ni91 primary particles are finer and more uniform, inheriting the precursor’s features, whereas D-Ni91 primary particles are coarse and densely packed. Cross-sectional analysis shows D-Ni91 has a dense structure, while G-Ni91 exhibits an interstitial-type structure with more voids inside, providing ample space and pathways for Li⁺ transport and accommodation of volume changes.

Figure 2. Structural and morphological analysis of the in-situ grown cathode.

4.2 Electrochemical Performance and Lithium-Ion Kinetics

G-Ni91 demonstrates superior electrochemical performance across various conditions. In the 2.7-4.3 V range, it shows higher first discharge capacity (212.4 mAh g⁻¹) and ICE (89.1%). At a high cut-off voltage of 4.5 V, G-Ni91 maintains an ICE of 88.5%, outperforming D-Ni91 (84.4%), indicating better structural stability and reversibility. This advantage persists at 50°C. In cycling tests, G-Ni91 achieves 92.6% capacity retention after 100 cycles at 1C, significantly better than D-Ni91’s 85.4%. Its superior rate capability, especially at high currents like 5C, benefits from the interstitial structure and lower cation mixing, facilitating fast Li⁺ migration.

Figure 3. Analysis of the cathode’s electrochemical performance under ambient, high-voltage, and high-temperature conditions.

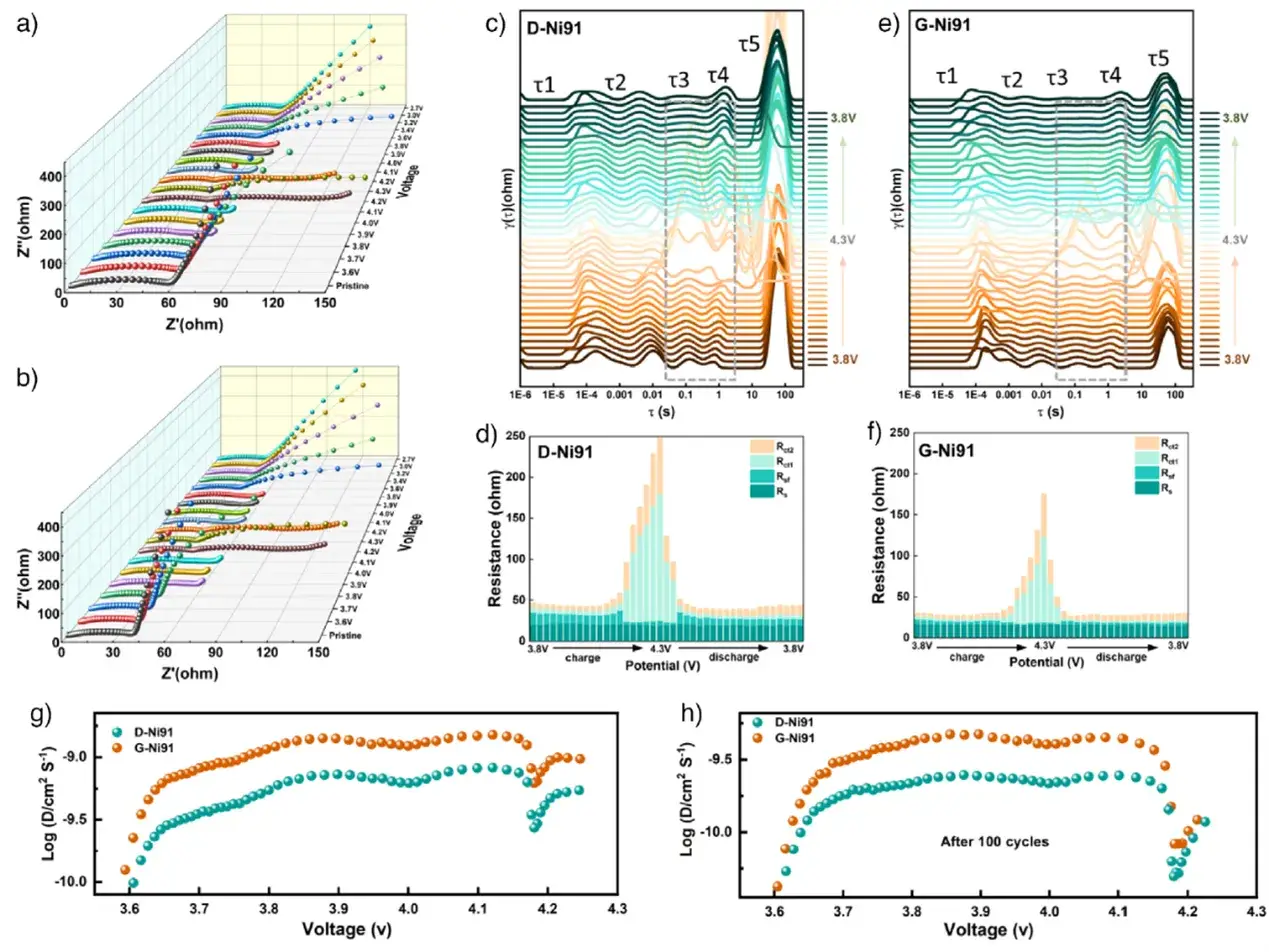

GITT tests show the Li⁺ diffusion coefficient for G-Ni91 (~2.02×10⁻⁹ cm²/s) is significantly higher than for D-Ni91 (~5.16×10⁻¹⁰ cm²/s) in the 2.7-4.3 V range. EIS and distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis reveal that G-Ni91 consistently exhibits lower charge-transfer resistance (Rct) before and after cycling. During charging to ~4.2 V, where the detrimental H2 ↔ H3 phase transition occurs, the increase in Rct is more pronounced for D-Ni91. These results confirm G-Ni91 possesses faster Li⁺ diffusion and lower interfacial impedance, underpinning its excellent rate capability.

Figure 4. Lithium-ion transport kinetics analysis and comparison based on in-situ EIS and GITT.

4.3 Structure-Performance Relationship and Degradation Analysis

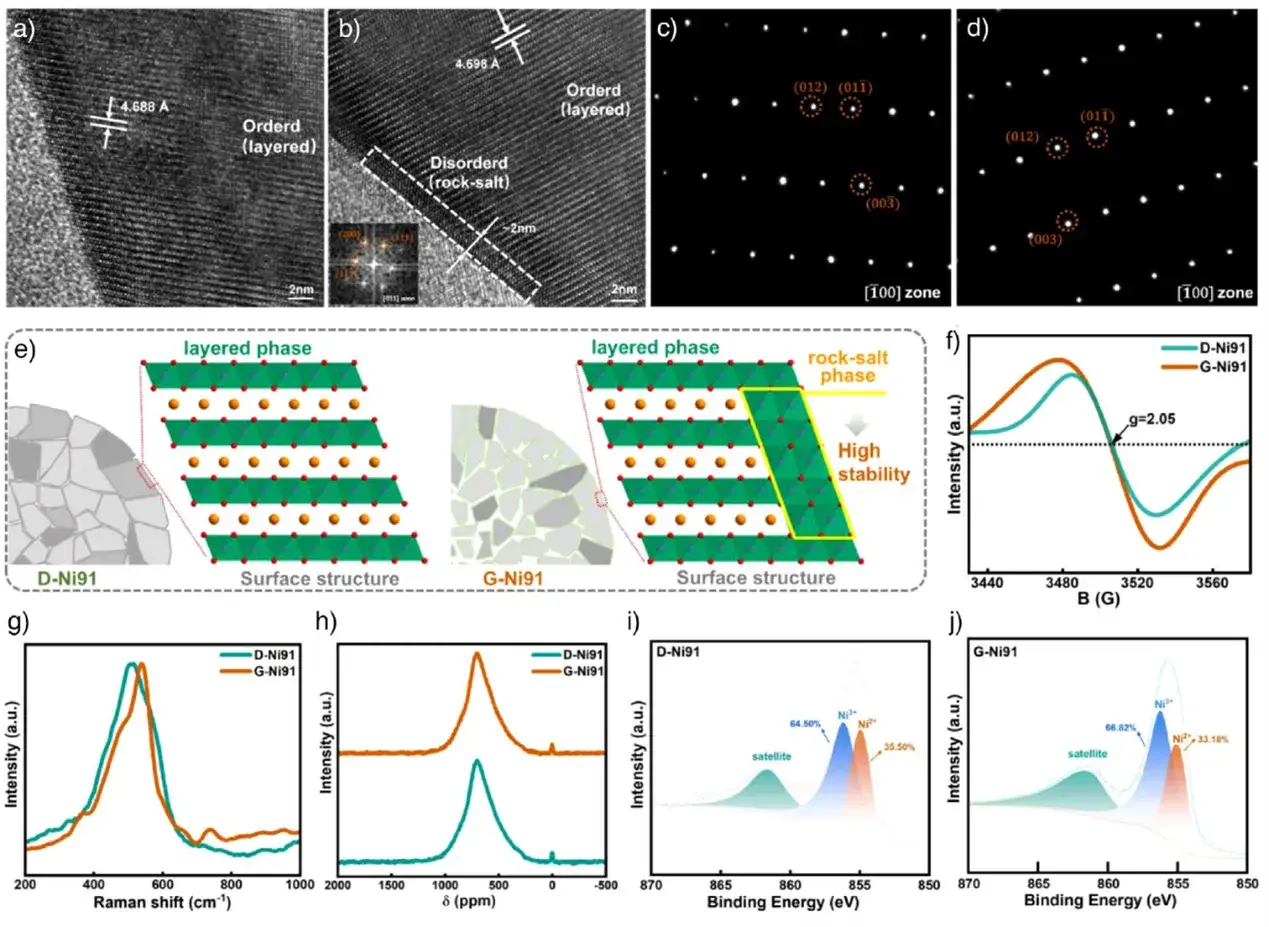

TEM reveals a ~2 nm thick rock-salt phase on the G-Ni91 surface, absent on D-Ni91. This 3D ionic framework is less dependent on lithium content and mitigates structural collapse at high delithiation, explaining the improved cycling stability. EPR and Raman spectra confirm the presence of oxygen vacancies and the rock-salt phase. The interstitial secondary structure promotes oxygen evolution during synthesis, driving surface reconstruction from layered to rock-salt. XPS shows a slightly lower Ni²⁺ proportion in G-Ni91 (33.18% vs. 34.5% in D-Ni91), indicating less cation mixing, which lowers Li⁺ migration resistance.

Figure 5. TEM, EPR, Raman, NMR, and XPS characterization and comparative structural analysis of the pristine cathodes.

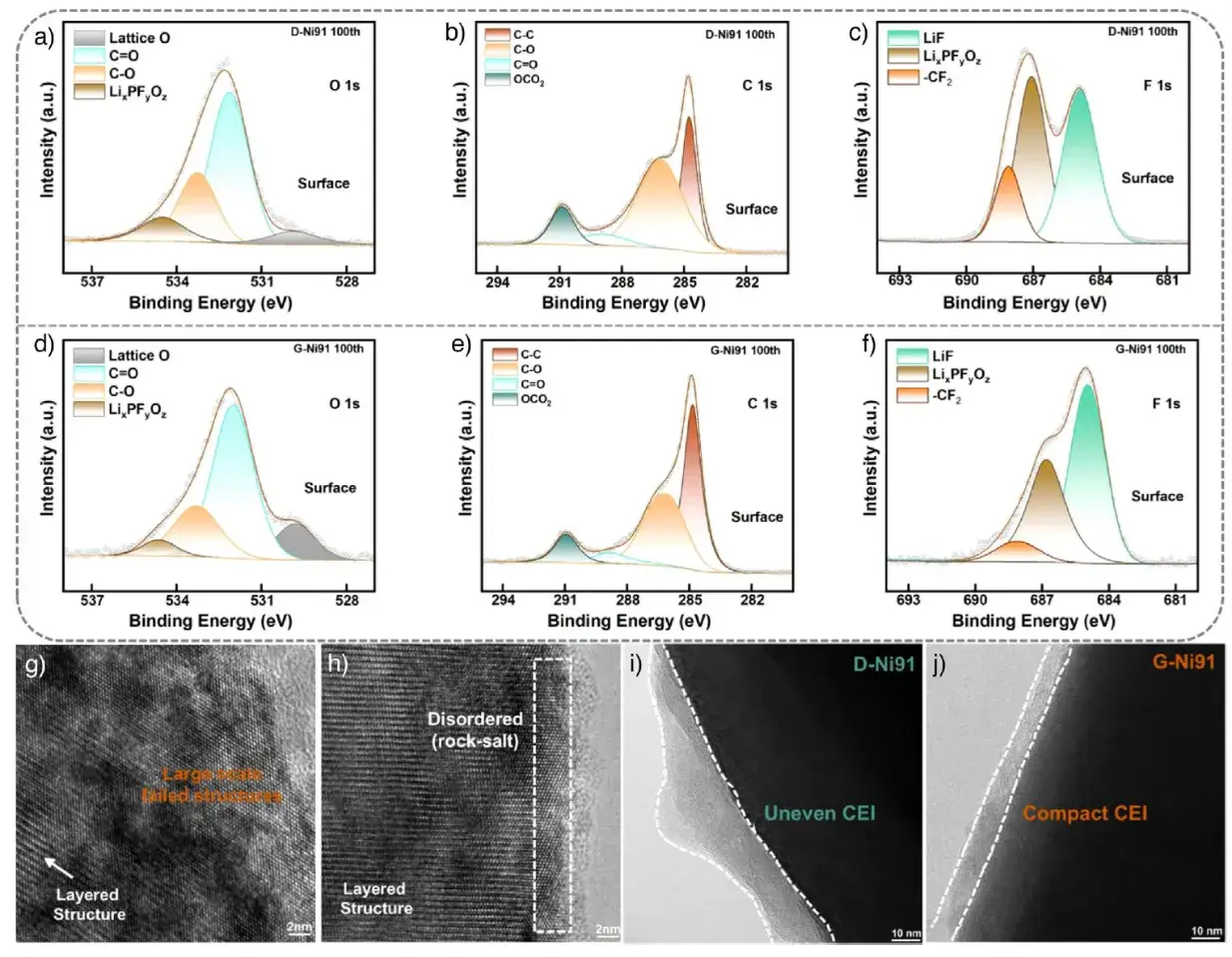

Post-cycling analysis via XPS and (cryo-)TEM shows G-Ni91 has a more stable cathode-electrolyte interphase (CEI) with stronger lattice oxygen signals, fewer organic by-products, and more stable LiF. Its surface rock-salt phase effectively suppresses lattice oxygen release and solvent decomposition. TEM confirms D-Ni91 surfaces become highly disordered after cycling, while G-Ni91 maintains a well-preserved layered structure beneath a thin, uniform CEI.

Figure 6. XPS, TEM, and Cryo-TEM analysis of the surface structure and CEI layer after cycling.

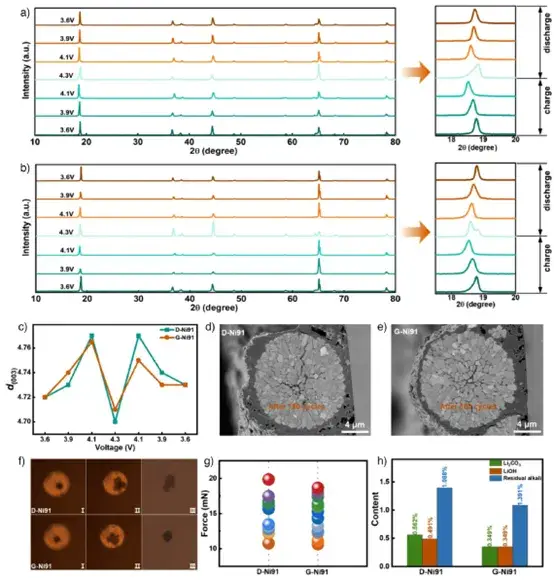

Ex-situ XRD shows G-Ni91 effectively suppresses the harmful H2↔H3 phase transition at high voltage, with smaller variations in (003) plane spacing, indicating better structural reversibility. Cross-sectional analysis post-cycling reveals superior integrity of G-Ni91 secondary particles; its interstitial structure accommodates volume changes, inhibiting crack formation. Single-particle compression tests confirm its mechanical strength meets compaction requirements. ICP results show significantly less transition metal dissolution for G-Ni91, indicating fewer interfacial side reactions.

Figure 7. Ex-situ XRD, post-cycling cross-sectional analysis, single-particle compression tests, and transition metal dissolution tests.

Contact Us

If you are interested in our products and want to know more details, please leave a message here, we will reply you as soon as we can.