-

iestinstrument

In-situ Expansion Analysis of Silicon-Carbon Cells Under Variable Pressure Conditions

1. Abstract

The expansion behavior of silicon-carbon cells is primarily attributed to the volumetric expansion of the silicon component. Excessive accumulation of irreversible expansion during cell cycling can lead to significant capacity degradation. Current industry strategies for enhancing the cycling performance of silicon-carbon composite electrodes include¹⁻⁴:

- Material Structural Modification: For example, reducing the size of silicon particles or synthesizing silicon electrodes with nanostructured architectures;

- Potential Control: To avoid the formation of crystalline Li–Si alloys;

- Development of Self-Healing Binders: To improve cohesion among active material particles;

- Utilization of Silicon Oxides: Which exhibit lower specific volumetric expansion during lithium insertion/extraction compared to crystalline silicon.

In addition to these material optimization approaches, the rate of cell expansion during operation can be mitigated by controlling the externally applied pressure. It is also noted that the chosen test pressure and control method significantly influence the measured expansion thickness and stress. In this article, the expansion behavior of silicon-carbon cells under various pressure conditions is compared using two test methodologies—constant pressure and constant gap—thereby providing researchers with a viable protocol for evaluating cell expansion.

![]()

Figure 1. Schematic Representation of Silicon-Based Electrode Degradation¹

2. Experimental Equipment and Methodology

2.1 Experimental Equipment

An IEST In-Situ Cell Swelling Testing System(Model IEST SWE2110) was used, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Exterior View of the SWE2110 Device

2.2 Test Cell Information:

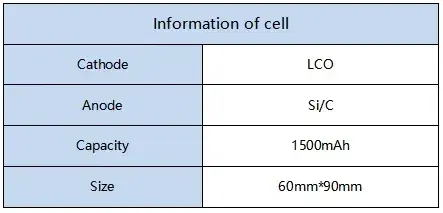

Details of the tested cells are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Test Cell Specifications

2.3 Testing Procedure for Cell Expansion

The cell under test is placed into the designated channel of the SWE2110. Using the MISS software, the corresponding cell identification numbers and sampling frequencies for each channel are configured. During the charging–discharging process, the software automatically records parameters such as cell thickness, thickness variation, stress variation, testing temperature, current, voltage, and capacity for subsequent comparative analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

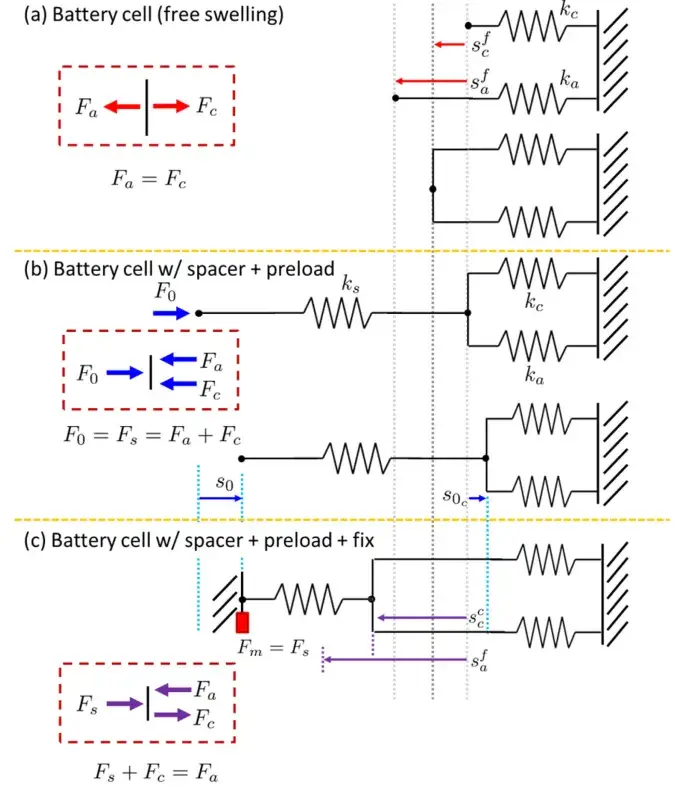

As illustrated in Figure 3, there are generally three modes for measuring cell expansion:

(a) Free Expansion Measurement without any external constraint;

(b) Cell Expansion Measurement under Constant Preload, wherein a constant preload (F₀) is applied;

(c) Cell Expansion Measurement under Constant Gap Conditions.

A battery can be modeled as two elements with equivalent stiffness: the internal cell (with equivalent stiffness kₐ) and the external casing (with equivalent stiffness k꜀).

Under equilibrium, the force analysis for the three conditions (see Figure 3) is as follows:

-

In the first case, the casing restricts the expansion of the internal wound electrode, and the forces on the casing and the wound electrode balance each other, resulting in a net zero external force.

-

In the second case, the externally applied preload (F₀) induces an initial displacement of the battery casing (denoted as s₀ and s0,c in Figure 3b). The binding plates on both sides enhance the effective stiffness (kₛ) perpendicular to the electrode. Under equilibrium, the preload F₀ (equal to the force Fs acting on both binding plates) is balanced by the sum of the forces on the wound electrode and the battery casing.

-

In the third case, when a constant measurement gap is maintained, the expansion behavior of the wound electrode and the casing deviates from that under free expansion due to the fixed gap condition.

Figure 3. Three modes for cell and module expansion testing, with force balance analysis⁵

4. Results: How Pressure and Modality Affect Measured Expansion

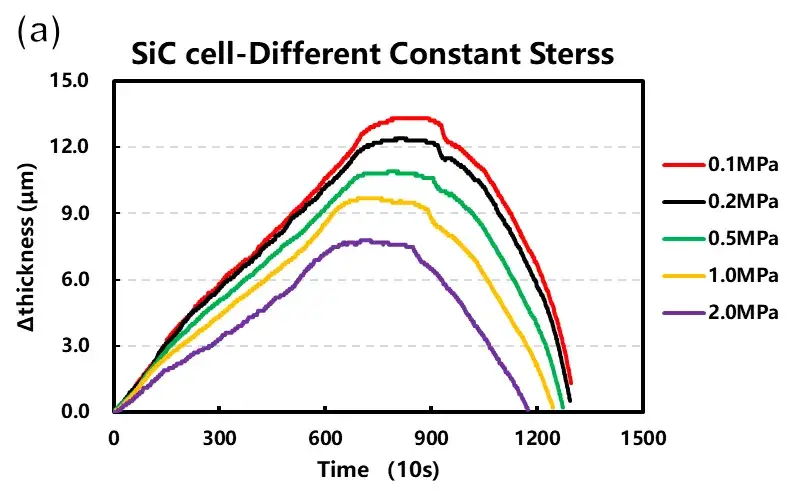

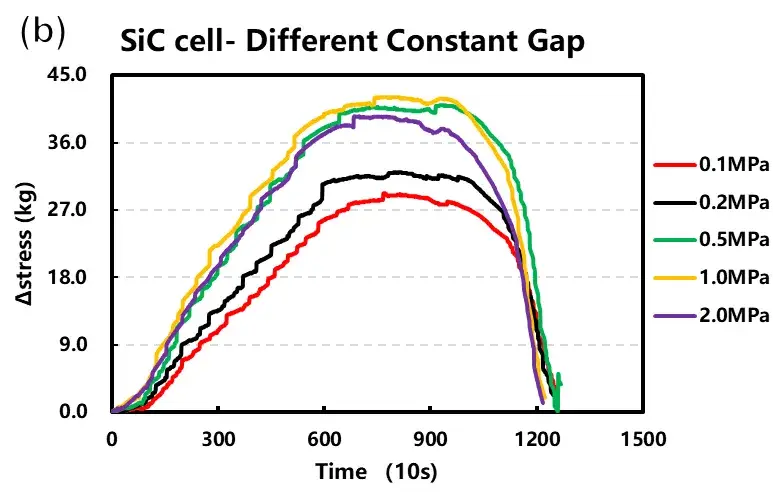

Parallel cells were tested under both constant pressure and constant gap conditions at varying initial loads (0.1 to 2 MPa). The resulting data curves are shown in Figure 4.

Key findings from the in-situ expansion analysis:

-

Constant Pressure Tests: As the applied constant pressure increased from 0.1 MPa to 2 MPa, the maximum expansion thickness during cycling progressively decreased. This confirms that external force can mechanically suppress outward swelling.

-

Constant Gap Tests: With an increasing initial preload force (0.1 to 2 MPa), the initial gap became smaller. The maximum expansion stress initially rose with preload but stabilized after reaching approximately 0.5 MPa.

-

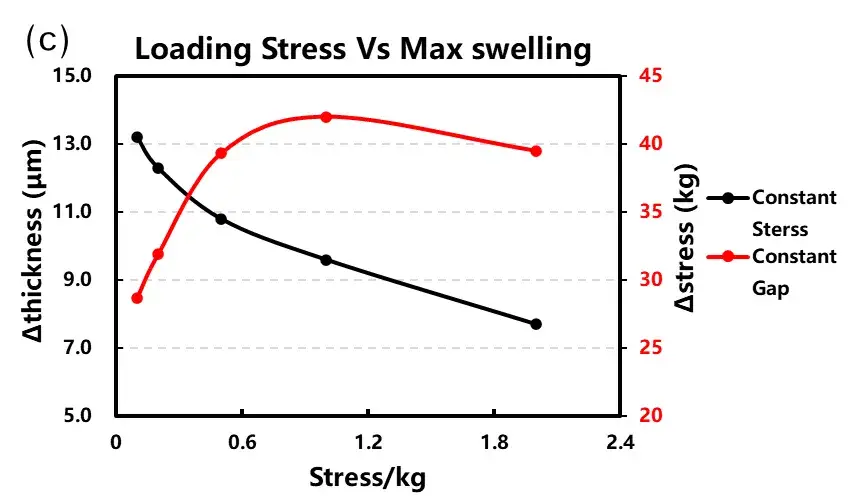

Trend Summary (Figure 4c): Expansion thickness shows a continuous, decreasing trend with increasing applied load. In contrast, the measured expansion force initially increases with load before plateauing.

Therefore, the magnitude and control method of the applied pressure profoundly impact expansion test results. Engineers must select the test scheme (constant pressure for thickness data, constant gap for stress data) that best aligns with their cell’s design and intended application conditions.

Figure 4. Cell charge curves and corresponding expansion data under (a) constant pressure and (b) constant gap modes. (c) Summary of maximum expansion thickness and force versus initial applied load.

5. The Underlying Mechanics: Stress, Strain, and Test Conditions

During charging–discharging, lithiation/delithiation in the lattice causes volumetric changes in active particles, generating internal stress fields. Concurrently, nonuniform stress due to diffusion may induce microcrack formation within the electrode. These microcracks can propagate during electrochemical cycling, leading to concomitant chemical and mechanical degradation and resulting in the capacity fade of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs). Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that appropriate external pressure can enhance interfacial contact and suppress dendritic lithium growth, thereby benefiting both liquid and solid electrolyte battery lifetimes and safety. In expansion testing, the interplay of external pressure and internal stress is critical.

Within the battery, electrochemical deformation comprises two components: reversible and irreversible. The reversible component refers to deformation that recovers its original configuration after electrochemical cycling, primarily due to lithium insertion/extraction and thermal effects. The irreversible component includes permanent plastic deformation and crack formation induced during lithiation/delithiation processes, arising from various side reactions such as active material dissolution, gas evolution, formation of surface layers (e.g., lithium plating, solid electrolyte interphase (SEI), cathode electrolyte interphase (CEI)), and electrolyte decomposition.

Lithiation-induced deformation is largely dependent on operating conditions (e.g., temperature range and voltage window) and is also closely related to electrode structure. For instance, the binder can affect deformation related to lithiation or side reactions, depending on its elastic modulus and adhesion properties; additionally, porosity plays a role—deformation may be accommodated by changes in porosity with the electrode dimensions remaining constant, or the electrode may maintain a constant porosity with the volumetric expansion resulting entirely in an increase in overall electrode dimensions. In summary, the volumetric changes in an electrode are strongly influenced by factors such as material porosity, particle arrangement, and mechanical properties.

The internal electrochemical stress in lithium-ion batteries is influenced by external constraints, the mechanical properties of the cell components, and the electrochemical deformation of the active material (AM). Higher external pressure can induce greater localized stress within the AM, increasing the likelihood of crack formation within particles to relieve internal stress. Additionally, external pressure may induce density variations; it can fragment particles into smaller sizes, thereby altering the particle size distribution. Various physical and mechanical properties of the particles—such as shape, coating materials, and elastic modulus—will affect the electrode response under external pressure.

Therefore, the choice of expansion testing conditions can influence the internal structural changes within the battery. For instance, high external pressure or a fixed gap condition that limits electrode expansion may in turn induce structural modifications such as crack formation to relieve stress, or allow active material expansion to fill available porosity. Consequently, the selection of testing conditions for volumetric expansion is critical and should closely mimic the conditions encountered during actual battery operation to accurately study battery degradation processes.

6. Conclusion

Using the SWE2110 In-situ Expansion Analyzer, this study compared silicon-carbon cell expansion under constant pressure and constant gap conditions. The results clearly demonstrate distinct trends: expansion thickness decreases with increasing load, while expansion force increases then stabilizes. This work underscores the importance of the test modality and pressure condition in characterizing cell swelling. Researchers and engineers should carefully select the testing scheme—prioritizing thickness data or stress data—based on their specific development and validation goals.

7. References

[1] I. Choi, J.L. Min, S.M. Oh and J.J. Kim, Fading mechanisms of carbon-coated and disproportionated Si/SiOx negative electrode (Si/SiOx/C) in Li-ion secondary batteries: Dynamics and component analysis by TEM. Electrochim. Acta 85 (2012) 369-376.

[2] M. Ashuri, Q.R. He and L.L. Shaw, Silicon as a potential anode material for Li-ion batteries: where size, geometry and structure matter. Nanoscale 8 (2016) 74–103.

[3] S. Chae, M. Ko, K. Kim, K. Ahn and J. Cho, Confronting issues of the practical implementation of Si anode in high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Joule 1 (2017) 47-60.

[4] X.H. Shen, R.J. Rui, Z.Y. Tian, D.P. Zhang, G.L. Cao and L. Shao, Development on silicon/carbon composite anode materials for lithium-ion battery. J. Chin. Cream. Soc. 45 (2017) 1530-1538.

[5] Oh K Y , Epureanu B I , Siegel J B , et al. Phenomenological force and swelling models for rechargeable lithium-ion battery cells. Journal of Power Sources, 2016, 310(Apr.1):118-129.

Contact Us

If you are interested in our products and want to know more details, please leave a message here, we will reply you as soon as we can.