-

iestinstrument

Analysis of Gas Evolution in Li-ion Cells During Overcharging: Role of Cathode and Electrolyte

1. Abstract

Gas evolution during overcharge is a critical safety and performance concern for lithium-ion cells. Using a dual-channel, temperature-controlled In-Situ Gassing Volume Analyzer (GVM2200), we performed in-situ overcharge tests on NCM523‖graphite pouch cells (nominal 1,000 mAh) to compare how two cathode variants (C1, C2) and two additive families (E1, E2) influence gas production. Cells were charged at 1C CC to 5.0 V at 25 °C while the instrument recorded real-time volume change, voltage, current and capacity. Our results show that (1) gas generation increases with additive loading (0 → 5 wt%); (2) one cathode (C2) releases substantially more gas than the other under identical conditions; and (3) additive chemistry shifts the onset potential for gas evolution. Notably, at 5% additive loading many cells failed to reach the 5.0 V setpoint, likely because rapid gas formation degraded electrode contact and increased polarization.

2. Introduction

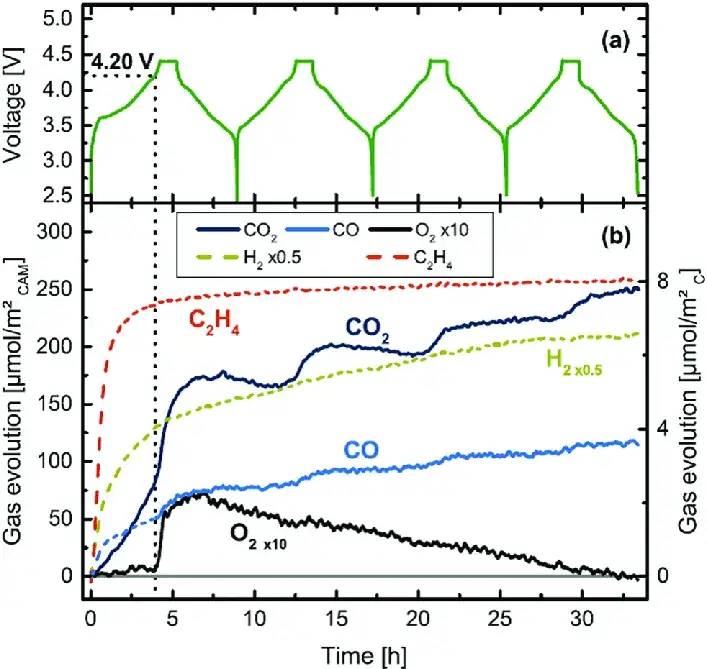

Lithium-ion batteries undergo a complex set of chemical and electrochemical reactions during overcharging. These include reversible phase transitions and irreversible structural changes in the electrode materials, as well as oxidation reactions of the electrolyte components. Particularly for Ni-rich cathode materials like NCM, structural instability at high voltages can lead to lattice oxygen release. This released oxygen can further oxidize the electrolyte, generating gases and causing cell swelling. Figure 1, adapted from literature, shows the gas composition changes during NCM811 overcharging monitored by in-situ OEMS¹. Therefore, probing gas evolution under controlled overcharge reveals both material vulnerabilities and electrolyte incompatibilities that would otherwise remain hidden in standard cycling tests.

Figure 1. In-situ gas composition monitoring of NCM811 during overcharging¹.

3. Experimental Equipment and Test Methods

3.1 Experimental Equipment

The GVM2200 system (IEST) was used for testing. This instrument, shown in Figure 2, operates within a temperature range of 20°C to 85°C and supports simultaneous dual-channel (2 cells) testing.

Figure 2. The Appearance of GVM2200

3.2 Test Parameters

Cells were charged at 25°C using a 1C constant current (CC) protocol until reaching a 5V upper voltage limit.

3.3 Test Method

Each cell was initially weighed (m₀). The test cell was then placed into the designated channel of the GVM. Using the MISG software, the cell ID and sampling frequency were configured. The software automatically recorded data for volume change, temperature, current, voltage, and capacity.

4. In-situ Overcharge Gas Evolution Analysis

4.1 Analysis of Charge Curves and Volume Expansion

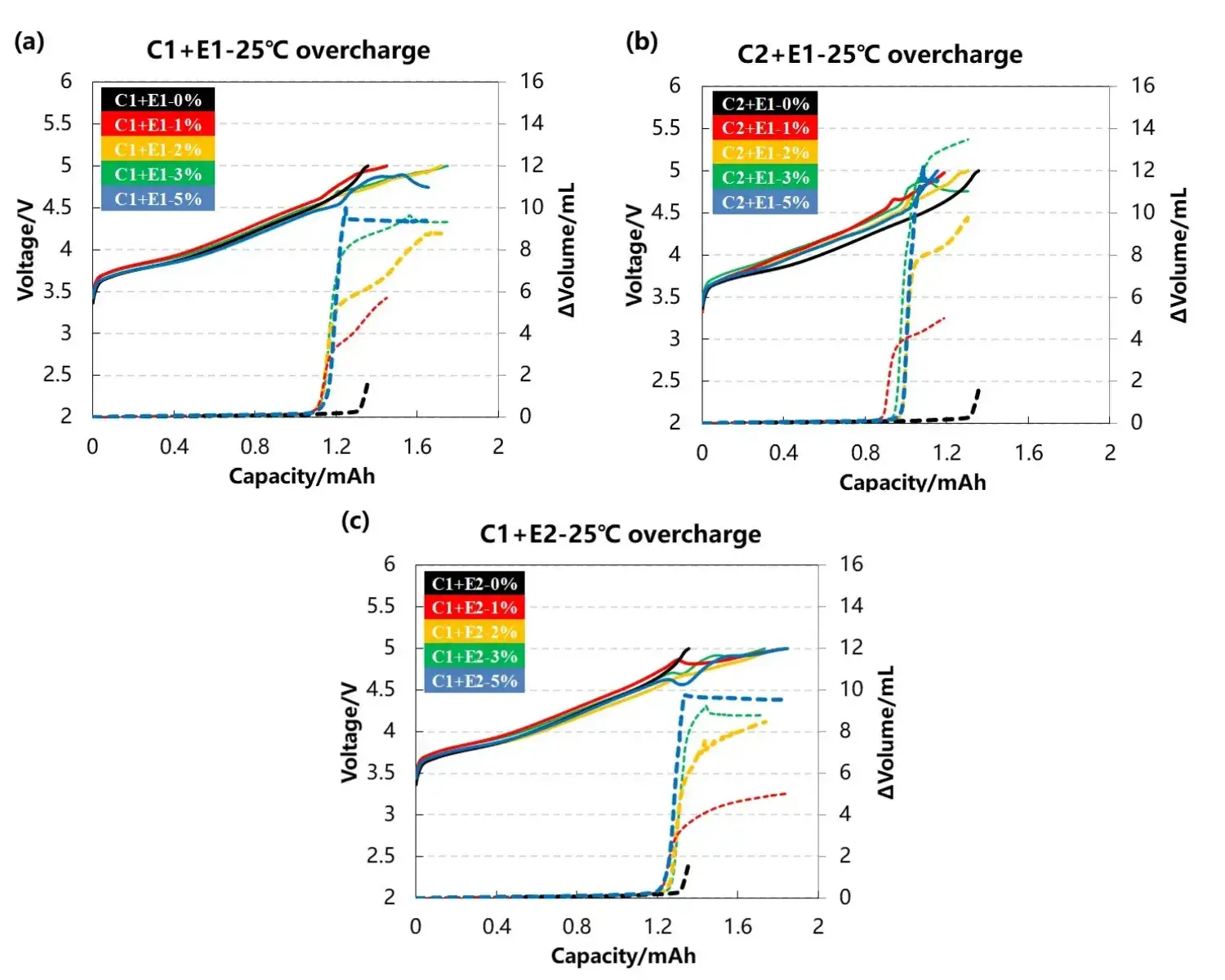

The voltage profiles and corresponding volume change curves for the cells are presented in Figures 3(a), 3(b), and 3(c). Two cathode materials, labeled C1 and C2, were paired with different electrolyte additive types, E1 and E2, at varying concentrations (0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, 5%).

Comparing Figures 3(a) and 3(b), which involve different cathode materials with the same electrolyte, the volume change increases significantly with higher additive content for both cell groups. This indicates that gas-producing reactions involving the additives are the primary cause of cell swelling. Furthermore, the total gas volume was consistently higher for cells containing the C2 cathode material. This suggests that C2 may possess inferior structural stability at high voltages, releasing more lattice oxygen to react with the electrolyte.

A comparison of Figures 3(a) and 3(c), which feature the same cathode material with different electrolytes, also shows increasing volume change with additive concentration. However, the total gas volume produced was nearly identical between the E1 and E2 groups at equivalent concentrations. This result implies that the type of additive does not significantly affect the total gas yield. Notably, in all three datasets, cells with 5% additive struggled to reach the 5V cutoff, likely due to excessive gas formation impairing interfacial contact between electrodes and increasing cell polarization.

Figure 3. Cell voltage and gas evolution curves for different cathode materials and electrolytes

4.2 Analysis of Total Gas Volume and Onset Voltage

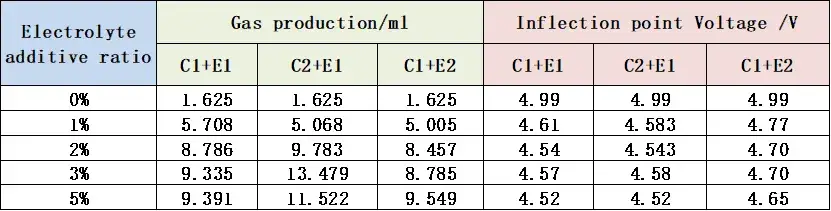

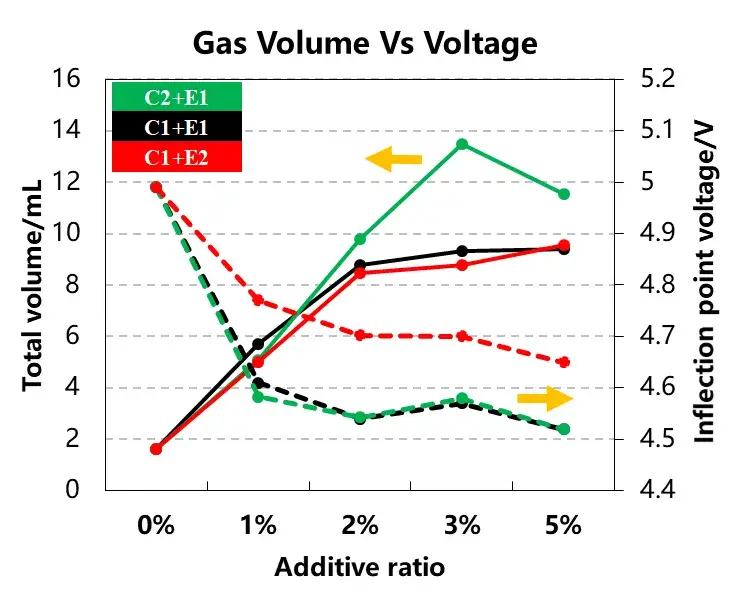

Table 1 and Figure 4 summarize the total gas volume and the inflection point voltage from the gas evolution curves for the three cell groups.

As the additive content increased, the total gas volume rose progressively for both E1 and E2 additive types. Cells incorporating the C2 cathode material consistently exhibited markedly higher total gas evolution. For a given additive type, increasing its concentration from 1% to 5% resulted in only minor shifts in the gas evolution onset voltage.

Therefore, both the cathode material type and the electrolyte additive concentration influence the total gas volume produced. In contrast, the additive type appears to have a more pronounced effect on the gas evolution onset potential. Selecting appropriate cathode materials, additive types, and their concentrations is crucial for managing gas evolution behavior during overcharging.

Table 1. Total gas volume and gas evolution potential information for cells with different cathode materials and electrolytes.

Figure 4. Gas volume and gas evolution voltage curves for different cathode materials and electrolytes.

5. Mechanistic interpretation (why gas evolution differs)

The observed patterns are consistent with two primary mechanisms:

-

Cathode lattice oxygen release: at high SOC and high potential certain layered oxides destabilize and release lattice oxygen; freed oxygen oxidizes electrolyte molecules, producing CO₂, CO and other gases. A cathode that releases more lattice oxygen (C2 in our tests) will therefore show higher gas output.

-

Electrolyte/additive oxidation pathways: additives can alter oxidative decomposition routes—either by forming protective CEI species or by generating reactive intermediates that accelerate gas formation. Higher additive concentrations increase the available reactant pool for oxidative gas-forming reactions, explaining the monotonic rise in total gas with additive wt%.

Importantly, these mechanisms interact: a cathode that releases oxygen at lower potentials can trigger additive oxidation earlier, amplifying gas evolution.

6. Summary

In this paper, using a temperature-controlled GVM2200, we quantified how cathode chemistry and electrolyte additive loading govern gas evolution during overcharge. Additive wt% increases correlated with higher total gas for both additive families; however, the cathode variant C2 produced significantly more gas than C1, pointing to material-dependent oxygen release as a key driver. Moreover, additive identity shifted the voltage window of gas onset—an actionable parameter for electrolyte formulation. In practice, combining cathode selection, additive tuning and in-situ gas monitoring offers a pragmatic route to control overcharge gas evolution and to reduce associated swelling and safety risks.

7. References

[1] Roland Jung et al. Oxygen release and its effect on the cycling stability of LiNixMnyCo2O2(NMC) cathode materials for Li-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164 A1361.

Subscribe Us

Contact Us

If you are interested in our products and want to know more details, please leave a message here, we will reply you as soon as we can.