-

iestinstrument

How SOC and SOH Influence Cell Compression Modulus — In-Situ Mechanical Characterization of Li-ion Batterry

1. Preface

Mechanical properties are an increasingly important performance axis for lithium-ion cells. In electric vehicles, cells experience external loads during assembly, thermal expansion in operation, and — critically — impact or crush events during collisions. These mechanical events interact with electrochemistry: a cell’s resistance to compression and its irreversible thickness change depend on how much lithium is stored (SOC) and how degraded the cell is (SOH). To offer useful, physics-based inputs for pack safety and multi-physics models, we measured cell thickness and compression behavior in-situ while varying SOC and SOH using an SWE2110 expansion/pressure analyzer.

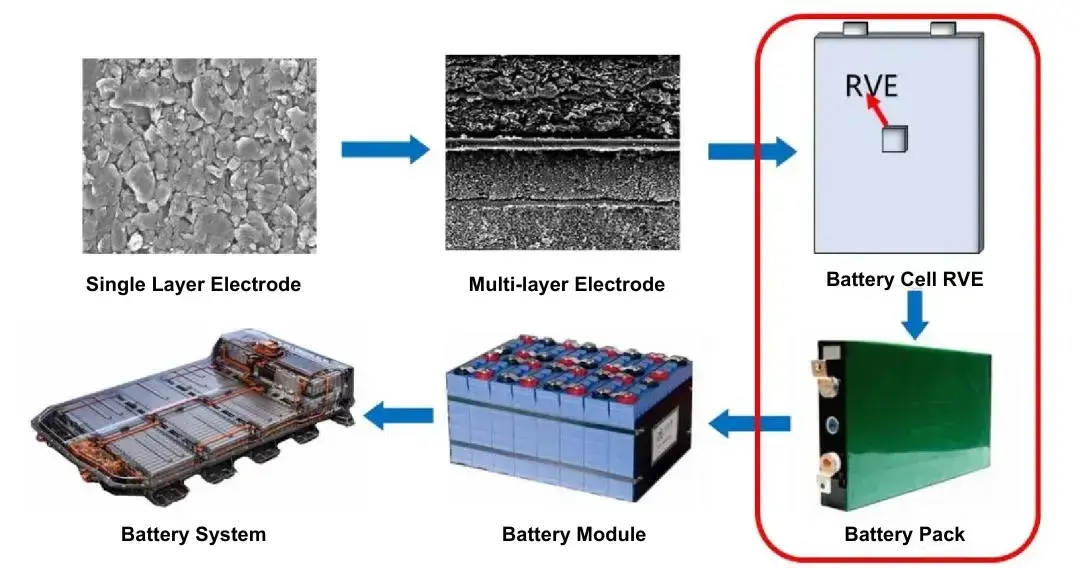

Mechanical testing is a fundamental approach to studying these properties. Research often follows a multi-scale hierarchy, encompassing micro-, meso-, macro-cell, and macro-system levels, as illustrated in Figure 1. These scales are interrelated yet distinct. At the single-cell level, a Li-ion battery is a sealed complex comprising cathode and anode electrodes, a separator, electrolyte, and an aluminum-plastic film or steel casing. Each component possesses unique mechanical characteristics, and their internal states continuously evolve with charge-discharge cycling and aging.

To offer useful, physics-based inputs for pack safety and multi-physics models, we utilizes an in-situ swelling analysis system (IEST) to evaluate the correlation between battery compression performance and key parameters like State of Charge (SOC) and State of Health (SOH). By monitoring pressure and thickness deformation, we assess how compression behavior varies with battery condition. This method provides a practical approach for studying the mechanical performance of Li-ion batteries under different states. The measured compression properties also serve as valuable theoretical data for supporting more accurate battery simulation and modeling.

Figure 1. Multiple research scales of lithium-ion batteries

2. Experimental Setup and Methodology

2.1 Experimental equipment

In-situ Swelling Analyzer, Model SWE2110 (IEST), as shown in the following picture:

Figure 2. Appearance of SWE2110 equipment

2.2 Test Information and Procedure

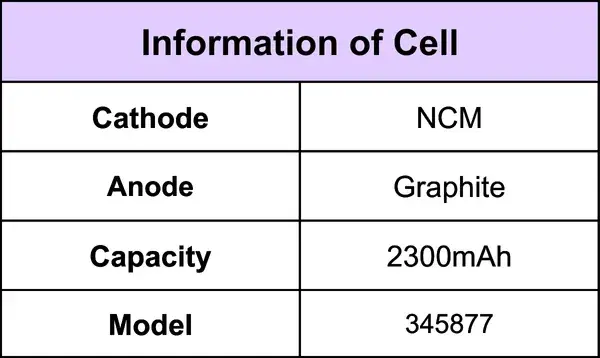

2.2.1 Battery information is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Test Battery Battery Information

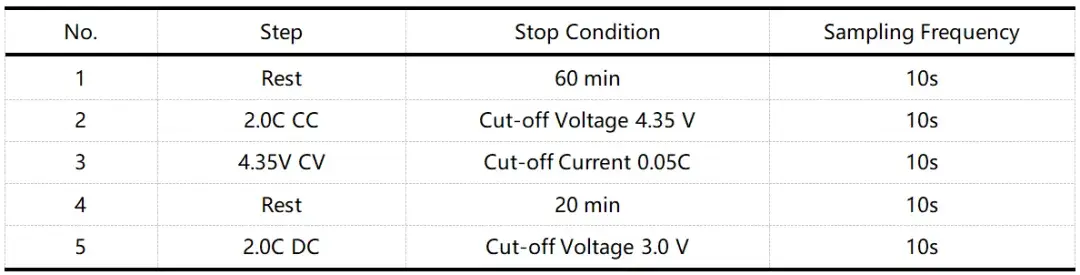

2.2.2 Charging and discharging process

The specific protocol is detailed in the provided flow chart

2.2.3 Compression Modulus Test

The test cell is placed in the corresponding channel of the SWE2110. Using the MISS software, we set the pressure control sequence, sampling frequency, and charge-discharge protocol. The software automatically records data including cell thickness, thickness variation, temperature, current, voltage, and capacity.

3. Results and Discussion

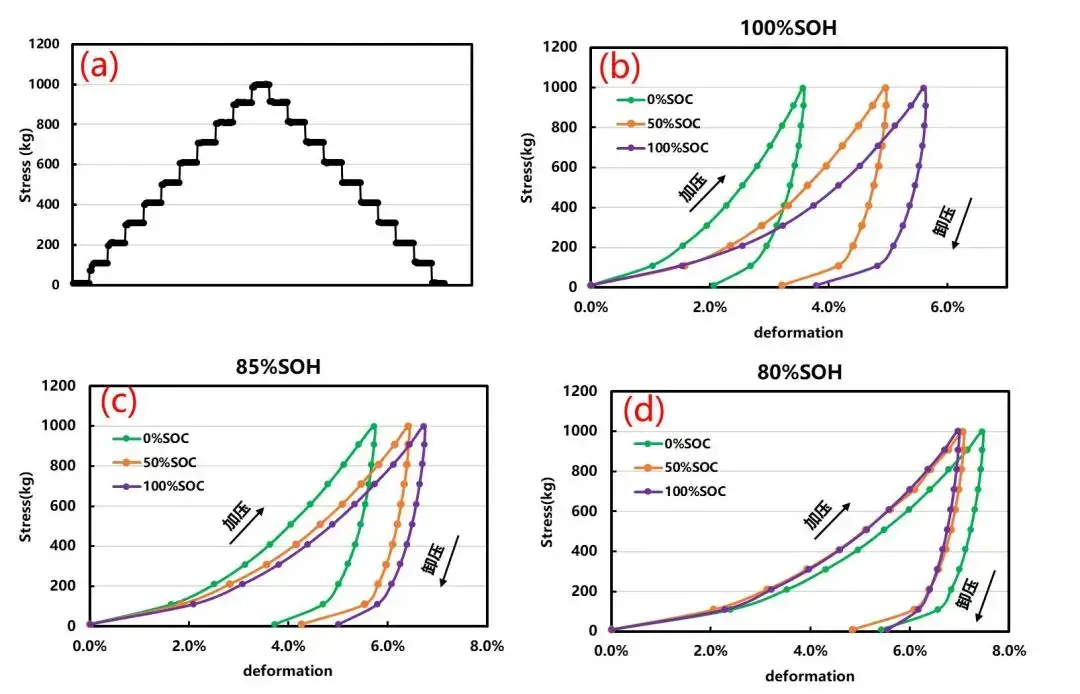

The in-situ swelling analyzer (SWE2110) was turned on in the compression experiment (steady state) mode, and the pressure adjustment was set as shown in Figure 3(a): the initial pressure was 10kg, pressurization step was 100kg, and each pressure was held for 10S until 1000kg, and then unpressurization was performed, and unpressurization step was 100kg, and each pressure was held for 10S until 10kg to complete the experiment.

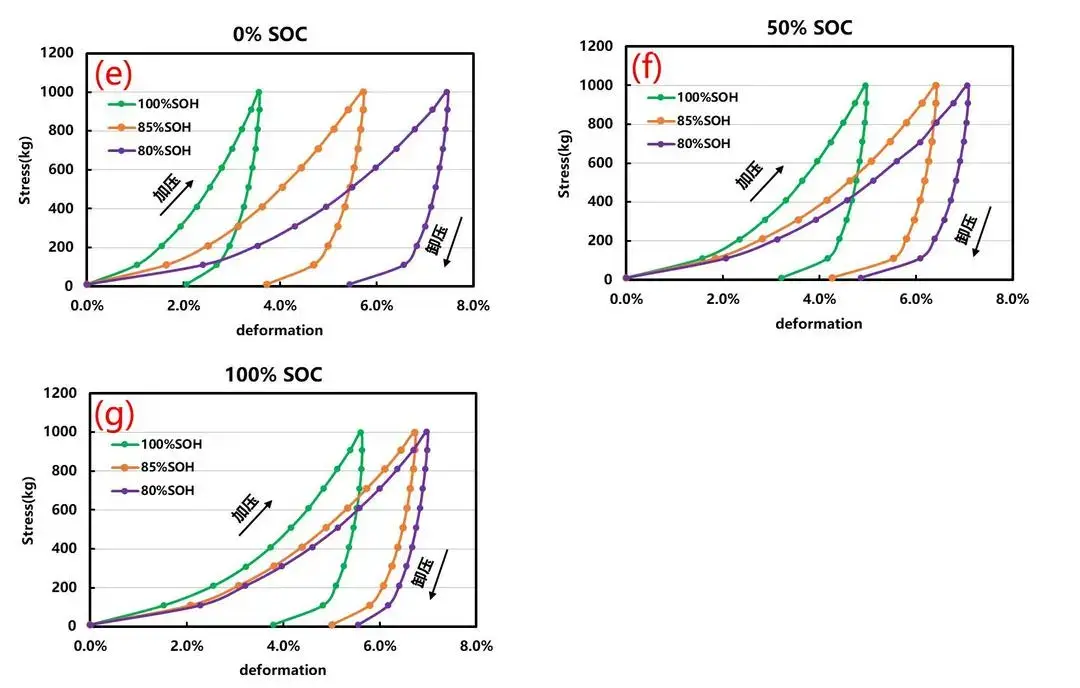

We performed this test on three fresh cells adjusted to different SOC states (0%, 50%, 100%). The results (Figure 3b) show that during the loading phase, the cell thickness decreases with increasing pressure, and recovers during unloading. Notably, the degree of compression varies with SOC. Batteries at higher SOC appear more compressible. This behavior is likely linked to the inherent properties and inhomogeneity of the active materials at different lithium de/intercalation states.

At different SOC levels, internal changes occur within the electrodes. For instance, in graphite anodes, lithium intercalation causes the crystal lattice to expand by up to 10% along the c-axis. Since graphite particles are typically aligned parallel to the current collector, this results primarily in thickness-direction expansion and contraction. This volume change induces slight deformation and reordering of microscopic particles and pores during (de)lithiation, affecting ion and electron transport. Consequently, non-uniformities in SOC and volume change arise through the thickness, potentially even causing localized top-electrode contraction and bottom-electrode expansion. Furthermore, the elastic modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and density of materials like graphite and Lithium Cobalt Oxide (LCO) change with their lithium content, leading to different mechanical responses.

We also conducted high-rate charge-discharge cycling to age the cells. Battery State of Health (SOH) was defined relative to initial capacity: 85% SOH at 85% retained capacity, and 80% SOH at 80% retained capacity. Comparing Figure 3(b), (c), and (d) reveals differences in compression behavior across SOH conditions for batteries at the same SOC. This indicates that the battery compression modulus is influenced not only by SOC but also by SOH. Furthermore, the influence of SOC appears to diminish as the battery ages (via high-rate cycling in this experiment).

During cycling and aging, battery performance degrades through various mechanical and chemical processes. Degradation mechanisms include current collector corrosion, morphological changes in active materials, electrolyte decomposition, formation and growth of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) layer, and material dissolution. Mechanical damage can also accelerate chemical degradation. For example, volume changes during intercalation generate significant stress within particles, leading to mechanical failure such as particle cracking or fracture. These cracks create fresh surfaces exposed to the electrolyte, promoting additional SEI formation and capacity fade. These degradation processes inevitably affect the electrode’s expansion and contraction behavior.

Figure 3.(a) Voltage regulation mode (b) (c) (d) Cell compression modulus curves at different SOHs

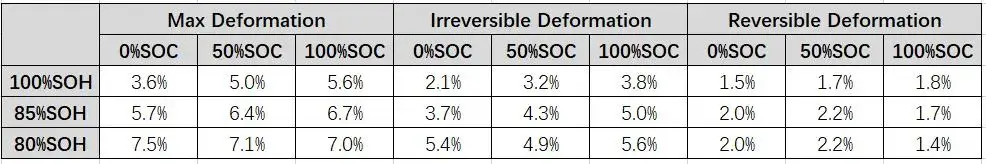

We further compared the compression performance at identical SOC states for different SOH levels. Figure 4 and Table 2 summarize the correlation between compression modulus and SOH. As SOH decreases, the maximum deformation increases, the compression modulus decreases, and irreversible deformation grows. This phenomenon may be attributed to several factors during high-rate aging: the rapid lithiation/delithiation of active materials causes structural changes, fragmentation, and dissolution. Concurrent side reactions lead to SEI growth, lithium plating on the anode, and gas generation. The fragmentation of active materials, SEI growth, and lithium plating contribute to increased irreversible deformation. Since the compression modulus of the SEI layer and lithium dendrites is much lower than that of the electrode sheets, the overall maximum compressible deformation of aged cells becomes significantly larger. Additionally, gas generation from side reactions alters the contact tightness between electrodes, further impacting compression performance. In summary, the battery compression modulus is closely related to its SOH.

Figure 4. Cell irreversible thickness variation curve

Table 2. Summary of battery compression performance

4. Summary

In this paper, the correlation between the compression performance of ternary/graphite system battery and SOC and SOH is analyzed by using the in-situ swelling analyzer (SWE) of IEST, and the experiments show that the compression performance of the battery is not static and unchanging, but varies with the SOC, SOH and other factors. The corresponding correlation can be used for related technicians to design more reliable products, provide more realistic data for simulation technicians, and improve the simulation effect.

5. References

[1] Yang Boda. Research on Mechanical Properties of Lithium-ion Power Battery for Electric Vehicles[D]. Hunan University

[2] Zhang J, Huang H, Sun J. Investigation on mechanical and microstructural evolution of lithium-ion battery electrode during the calendering process[J]. Powder Technology, 2022, 409: 117828.

Contact Us

If you are interested in our products and want to know more details, please leave a message here, we will reply you as soon as we can.