-

iestinstrument

Elastic-Plastic Analysis of Different Particle Size LCO Powders During the Powder Compaction Process

1. Abstract

Powder compaction behavior directly shapes how electrode coatings densify during manufacturing, and it therefore influences electronic connectivity, mechanical integrity and electrochemical performance. This study examines the powder compaction process of four lithium cobalt oxide (LCO) powders with different particle sizes and quantifies their elastic and plastic behaviour under controlled compression. Using stepped-pressure testing and Heckel analysis, we extract actionable metrics that help formulators and process engineers select powders and set calendaring windows.

2. The Micromechanics of Powder Compaction

Dense materials deform under force following the principles of mass conservation and volume constancy. In contrast, powder deformation is more intricate. The pressing deformation of a powder mass obeys only mass conservation. Powder deformation encompasses both the deformation of individual particles and the alteration of pore morphology between particles, meaning particles undergo displacement.

During compaction, the following microscopic deformation mechanisms occur:

-

Particle Rearrangement: Electrode particles realign under stress. Initially irregularly arranged particles gradually adopt a tighter packing configuration. The number of contact points between particles increases, filling the original pore space.

-

Particle Repacking: With increasing external stress, initially dispersed electrode particles form local aggregates. These particle assemblies fill local regions of the powder, creating a denser structure. This repacking process reduces inter-particle gaps and enhances the compactness of the electrode.

-

Particle Compression Deformation: Under stress, electrode particles undergo compressive deformation. The contact area between particles increases, leading to tighter contact and mutual extrusion, which reduces the number and size of pores.

-

Particle Compression and Fragmentation: During compaction, secondary electrode particles may crack or fracture. This crushing phenomenon alters the overall powder morphology and related properties such as conductivity.

The elastic and plastic behaviour during the powder compaction process determines the final compact’s density and its tendency to relax (spring-back) after the calender nip. Understanding this balance is crucial for consistent electrode manufacturing.

The following section introduces experiments and an empirical equation to quantitatively assess the elastic-plastic mechanical behavior of powder during the compaction process.

3. Experimental Process

3.1 Materials & Equipment

Four different LCO powder samples, with varying average particle size (designated LCO-1 to LCO-4, where LCO-4 < LCO-2 < LCO-3 < LCO-1), were analyzed(LCO-4 being the finest). The test instrument was a IEST Powder Resistivity & Compaction Density System(PRCD3100), which applies precise uniaxial pressure while measuring the thickness of the powder compact in real-time.

3.2 Test Protocol

A stepwise pressure profile from 10 MPa to 200 MPa (in 20 MPa increments) was applied, with a 10-second hold at each step to ensure stress equilibration and accurate measurement.

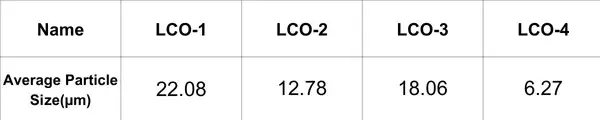

Table 1. Average particle size of four LCO powders

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of experimental materials and instruments: (a) Four LCO Powders with a mass of 2 g; (b) Internal diagram of powder compaction detector; (c) External diagram of a PRCD3100; (d) procedure of powder compaction experiment.

4. Mechanical Analysis Tool: The Heckel Equation

The porosity-pressure relationship is commonly expressed by the Heckel equation, which is a semi-empirical formula summarizing the relationship between compressive stress and density change, and has the following expression:

In[1/(1-D)]=kp+A

where p is the pressure; D is the relative density of the powder column when the pressure is p; k and A are constants that can be obtained from the slope and intercept of the straight line portion of the relationship between In[1/(1-D)] and p. The physical significance of A can be understood by A=In[1/(1-Dρ)], where D is the relative density and ρ is the maximum density of the particles before the particle deformation after the particles have been rearranged at low pressure. This value may be closely related to the true density, morphology, particle size distribution, etc. of the Li-ion battery electrode powder. k is a parameter that measures the size of the powder plasticity. the larger the value of k, i.e., the larger the change in density caused by the same change in pressure, the larger the plasticity of the powder. The experimental results show that when k is a constant, In[1/(1-D)] and p are in a straight line, indicating that the relative density change of the powder is caused by plastic deformation; if k is a variable, then In[1/(1-D)] and p are in a curvilinear relationship, indicating that the relative density change is caused by the rearranging, crushing and so on. We use Heckel fits to rank LCO powders by their expected behaviour in the industrial powder compaction process.

5. Results: Linking Particle Size to Deformation Mechanics

5.1 Heckel Analysis Reveals Compressibility Trends

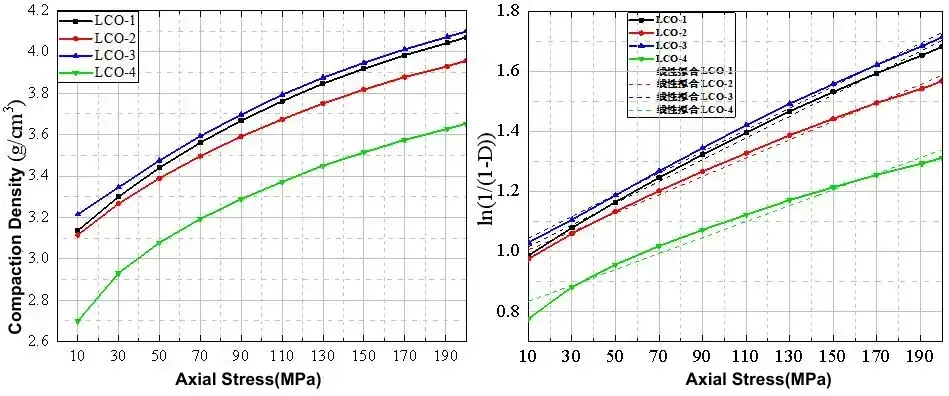

The stress-compaction density relationship curves and Heckel fitted straight lines for the four LCO powders are plotted in Figure 2, in which LCO-1 and LCO-3 specimens have larger k values, indicating that under the average particle size and particle size distribution of these powders, LCO-1 and LCO-3 have poorer filling of pores by displacement and rearrangement of particles under the same pressure, while the particles undergo a large elasto-plastic deformation.LCO -4 has the smallest k, and LCO-4 lithium cobaltate particle size is the smallest, from which it can be assumed that smaller particles are displaced and filled more densely, and the particles have more contact points with each other. Its small particles achieve efficient packing and rearrangement early in the powder compaction process, resulting in less additional plastic densification at higher pressures and a greater relative contribution from elastic interactions. As a result, the density change under increasing the same pressure is small, and more elastic strain and less plastic deformation occurs under particle interaction. Figure 3 shows the deformation pressure curves of the four LCO powders under different pressures. The pressure and displacement curves of the powders can be obtained after a simple conversion, and the area enclosed under the curve is the energy required for the occurrence of strain in the material.

Figure 2. Stress-compaction density curves and Heckel plots for the four LCO powder samples

5.2 Energy Decomposition: Quantifying Elastic vs. Plastic Work

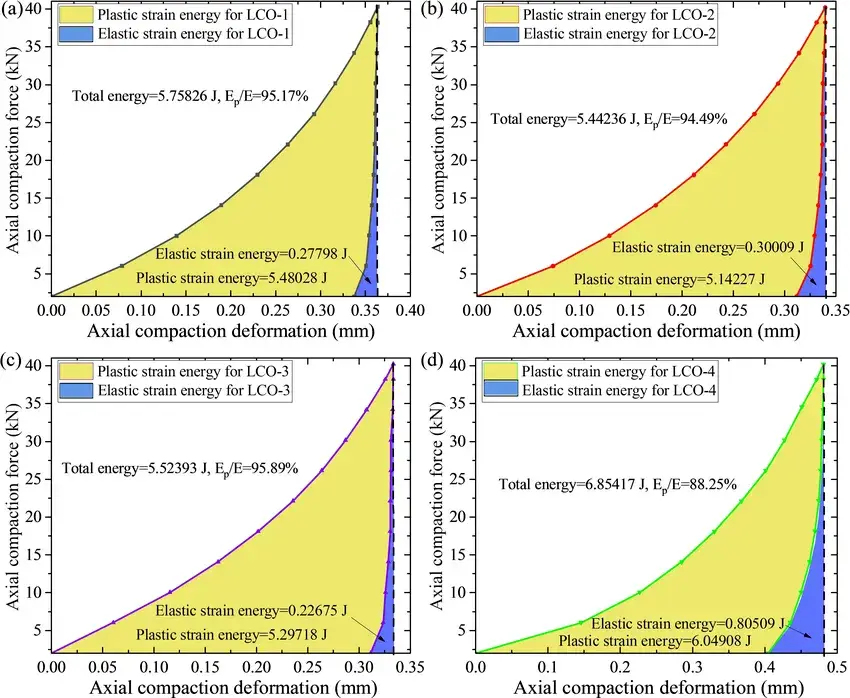

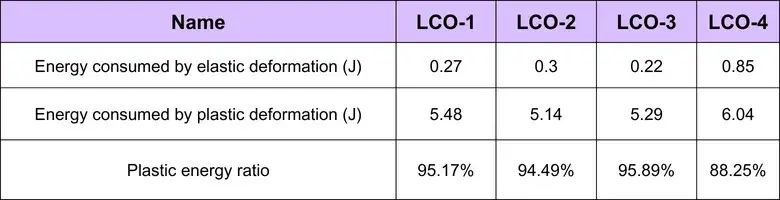

The area enclosed by the grid area in Figure 3 represents the energy required for plastic deformation of the LCO powder during compaction, the area enclosed by the vertical line through the highest point of the deformation curve and the horizontal axis is the total work done by the indenter on the powder, and the difference between the total work and the energy consumed by the plastic deformation is the energy consumed by the elastic deformation. The following table shows the energy consumed by elastic deformation, the energy consumed by plastic deformation, and their respective percentages for the four lithium cobalt oxide powders under this condition.

The data demonstrates a key finding: finer LCO powder (LCO-4) exhibits a higher percentage of elastic energy consumption and more pronounced spring-back, while coarser powders consume a greater fraction of energy in plastic work.

Figure 3. (Top) Deformation curves under different pressures. (Bottom) Table quantifying the energy distribution between elastic and plastic deformation for each LCO powder.

Table 2. Energy consumption for elastic and plastic deformation of four LCO powders

6. Energy partitioning: How Much Work is Plastic vs. Elastic?

We integrated pressure–displacement traces to partition input mechanical work into plastic (irreversible) and elastic (recoverable) components:

-

Total input work equals the area under the loading curve up to peak displacement.

-

Plastic work corresponds to the irreversible portion (area that does not recover during unloading).

-

Elastic work is the recoverable area observed as rebound on unloading.

Across the tested LCO powders, plastic deformation accounted for roughly ~90% of the mechanical work, indicating predominantly irreversible compaction under these conditions. Finer powders (LCO-4) showed higher elastic fractions and correspondingly smaller plastic-work shares, consistent with lower Heckel kkk values. These energy metrics help predict the degree of particle fracture and surface-area increase introduced by calendaring.

7. Micro-mechanisms Explaining the Macroscopic Response (Role of Particle Size)

Several interacting microscale processes produce the observed trends:

-

Particle rearrangement: dominates at low pressures; particles reposition to fill voids with minor permanent strain.

-

Elastic compression: particles elastically deform under moderate stress and partly rebound on unloading; this mode is more prominent in finer powders.

-

Plastic deformation & fragmentation: at higher local contact stresses particles plastically flow or fracture, creating permanent densification and new fines; coarser powders in this dataset showed more fragmentation.

Because contact stresses are heterogeneous, localized fracture can occur even when nominal pressure seems moderate. Therefore, particle-scale heterogeneity (shape, internal flaws) amplifies the effect of nominal pressure in the powder compaction process.

8. Practical Implications for Electrode Manufacturing and Calendaring (Particle Size Considerations)

From a process-engineering viewpoint, these findings yield specific guidance:

-

Powder selection trade-offs: finer LCO powder (smaller particle size) can reach target packing density with less fragmentation and lower introduction of new surface area, which helps preserve electrochemical stability. However, excessive fines elevate slurry viscosity and may impair coating performance.

-

Calendaring pressure windows: derive pressure setpoints from Heckel-based ranking (slope kkk and intercept AAA). Avoid pressures where coarser powders enter aggressive fragmentation regimes—verify by post-calender particle-size distribution (PSD) checks.

-

Energy budgeting: because ~90% of mechanical work is plastic under these test conditions, densification will be largely irreversible; avoid relying on elastic rebound to recover porosity.

-

Quality control: monitor incoming particle-size distributions and set acceptance bands; small shifts in PSD can accumulate and cause stack-level nonuniformities in multilayer assemblies.

9. Summary

-

Particle Size Dictates Spring-back: Finer LCO powder consistently demonstrates greater elastic recovery post-compaction, a critical factor for predicting final electrode thickness after calendering.

-

Heckel k as a Predictive Parameter: The Heckel constant k serves as a valuable, quantitative indicator of a powder’s compaction mechanism, correlating lower k values with finer sizes and a higher degree of elastic and plastic behaviour.

-

Process Design Insight: For formulations using fine LCO powder, process parameters must account for significant spring-back to hit density and porosity targets consistently. This quantitative analysis moves electrode process design from trial-and-error towards a more predictive, mechanistic approach.

10. References

[1] YANG Shaobin,LIANG Zheng. Principles and applications of lithium-ion battery manufacturing process[J]. [2023-07-08].

[2] Kai W, Jw A, Yx A, et al. High voltage lithium cobalt oxide materials for rechargeable Li-ion batteries[J]. Journal of Power Sources, 460.

[3] Park M, Zhang X, Chung M, et al. A review of conduction phenomena in Li-ion batteries[J]. Journal of Power Sources, 2010, 195(24):7904-7929.

Contact Us

If you are interested in our products and want to know more details, please leave a message here, we will reply you as soon as we can.