-

iestinstrument

Identifying the Lithium Plating C-rate Window in Li-ion Pouch Cells via Non-Destructive Expansion Analysis

1. Abstract

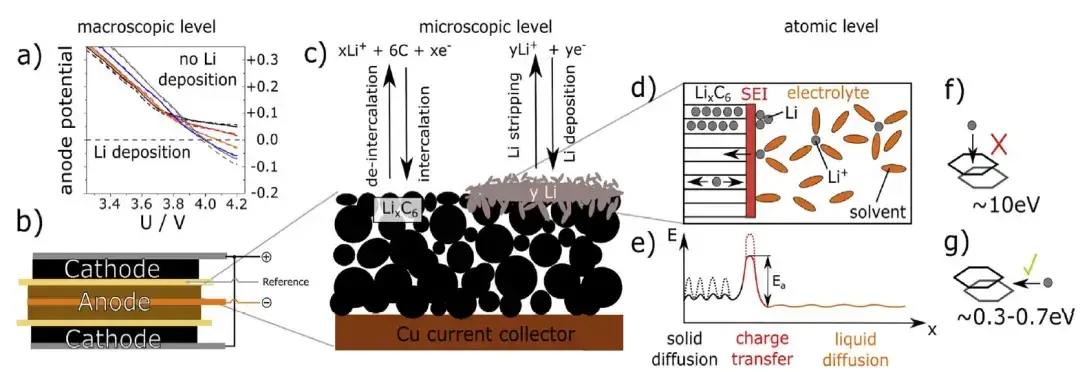

Lithium plating is a critical failure mode during fast charging—especially at low temperatures—because plated Li reduces capacity, forms electrically “dead” Li, consumes electrolyte via SEI formation, and can grow dendrites that puncture separators. This application describes a practical, nondestructive method to identify the SOC/voltage/rate/temperature window for lithium plating in LCO‖graphite pouch cells using an in-situ thickness swelling analyzer (SWE2100, IEST). We present the test protocol, experimental results at 5°C across charge rates from 0.2C to 1.5C, post-mortem validation, and how to translate observed thickness signatures into a plating onset window to guide safe fast-charge strategies.

2. Why Identify Lithium Plating Windows?

When a cell is charged faster than the negative electrode can accept Li⁺ into its host lattice, excess Li⁺ reduces to metallic lithium on the anode surface. This lithium plating (often dendritic or mossy) presents three primary risks:

-

Mechanical and safety risk: lithium dendrites may penetrate the separator and provoke internal short circuits, thermal runaway, or fire.

-

Capacity loss: plated Li can detach and become electrically isolated (“dead Li”), reducing Coulombic efficiency and usable capacity.

-

Aging acceleration: fresh Li metal reacts with electrolyte to form additional SEI, increasing resistance and consuming electrolyte.

For pack design and battery management, accurate knowledge of the charge rate / SOC / temperature windows that trigger plating is essential to specify safe fast-charge limits.

Figure 1. Analysis the causes and risks of lithium plating 1

3. Detection Approaches: pros and cons

Common plating detection methods fall into three families:

-

Direct anode potential vs Li/Li⁺ — using a reference electrode or half-cell measurement detects potentials below 0 V vs Li/Li⁺ (thermodynamic threshold for Li metal deposition). However, integrating reference electrodes into commercial cells is invasive, can perturb electrochemistry, and is impractical for production screening.

-

Electrical/electrochemical proxies — capacity fade, impedance growth (EIS), and differential voltage or differential capacity analyses can indicate plating indirectly. These are practical but may miss early or partially reversible plating since some plated Li can re-intercalate or dissolve later.

-

Post-mortem inspection — cell teardown with visual/SEM/XPS confirmation provides direct evidence but is destructive and low throughput.

To provide a sensitive, noninvasive, and relatively fast diagnostic, we used In-situ Thickness Swelling Tester as a plating indicator. Thickness increases associated with metallic Li deposition are larger than purely intercalation-driven volume changes and therefore serve as an early, high-resolution signal for plating.

4. Experimental Setup

4.1 Test Equipment

The experiments utilized an IEST In-situ Thickness Swelling Analyzer (Figure 2). This instrument applies a controllable force range of 50–10,000 N and operates within a temperature chamber spanning -20°C to 80°C.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of the in-situ swelling analyzer(SWE Series)

4.2 Cell Information:

The test cell specifications are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Cell Information

| Material | LCO/ Graphie |

| Capacity | 2400mAh |

| Voltage | 3.8V |

| Model | Pouch cell-345877 |

4.3 Testing Procedure

Cells were placed inside the analyzer’s temperature-controlled chamber set to 5°C. They were charged at constant currents corresponding to 0.2C, 0.5C, 0.8C, 1.0C, and 1.5C rates, with a cutoff current of 0.05C. Discharge was performed at a constant 2A. Throughout cycling, the analyzer continuously monitored thickness change under a constant 5 kg force.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1 Key observations at 5°C: Expansion Signatures and Rate Dependence

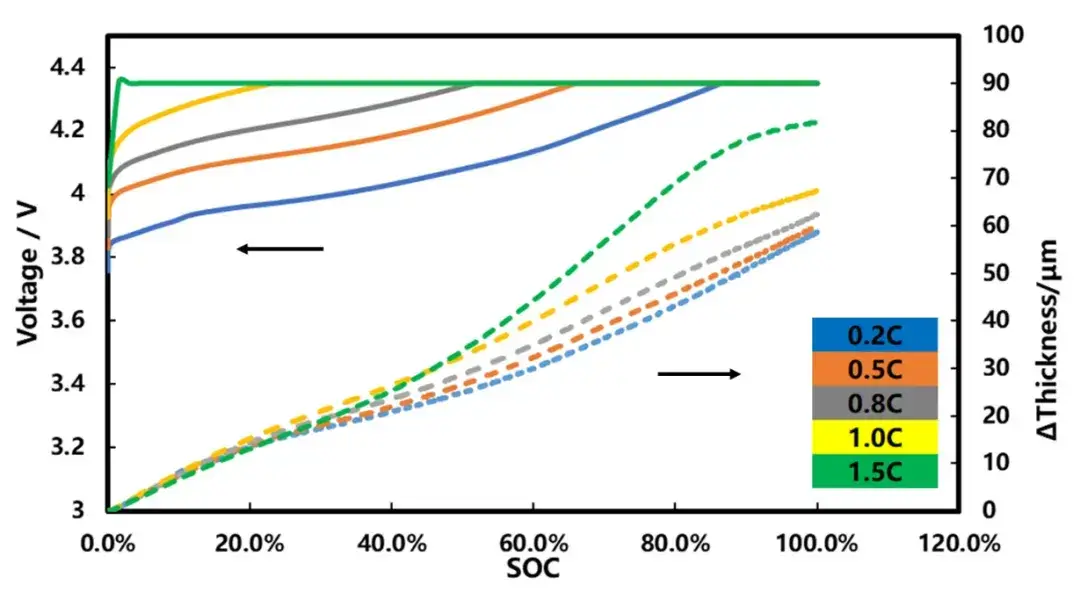

Figure 3 shows the voltage and thickness expansion curves for the pouch cell charged at five different C-rates at 5°C. When the cells were charged at the five rates above, the measured maximum thickness expansions at full charge were:

-

0.2C: 58.7 μm → 1.82% expansion

-

0.5C: 60.0 μm → 1.86%

-

0.8C: 62.4 μm → 1.92%

-

1.0C: 67.4 μm → 2.09%

-

1.5C: 87.1 μm → 3.75%

Notably, the 1.0C and 1.5C curves diverge from the lower-rate curves at higher SOCs: the slope of thickness vs SOC (dthickness/dSOC) increases sharply for 1.0C and dramatically for 1.5C. This slope inflection indicates an additional volumetric process beyond graphite intercalation—consistent with metallic Li deposition on the anode surface. In other words, lithium plating signatures emerged at and above ~1.0C under these 5°C conditions.

Figure 3. Charging curve and thickness change curve of different ratios

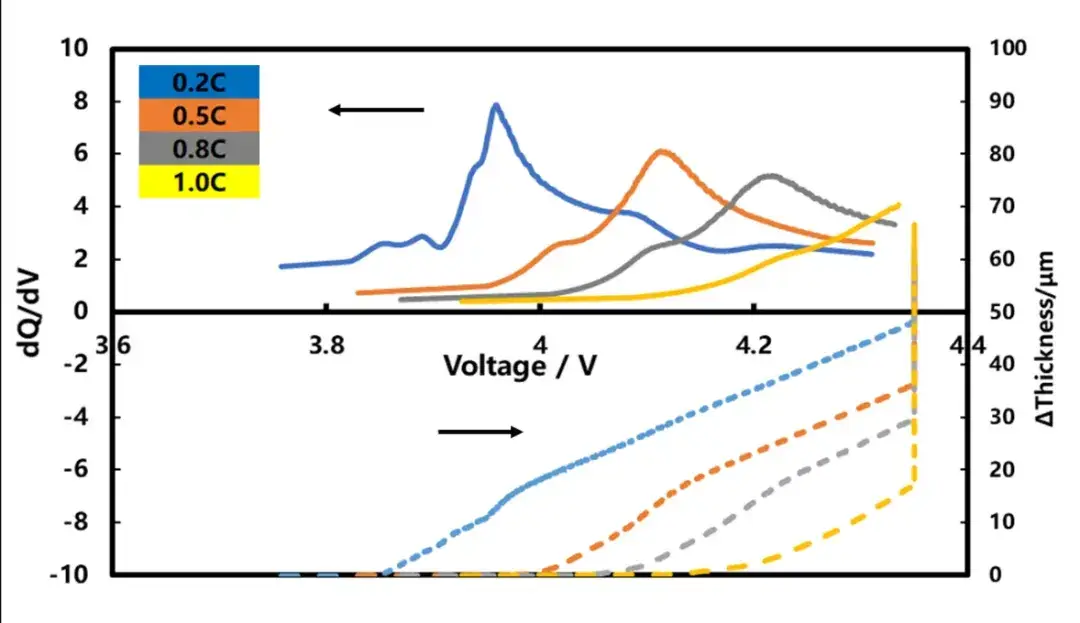

5.2 Correlating Expansion With Differential Capacity (dQ/dV)

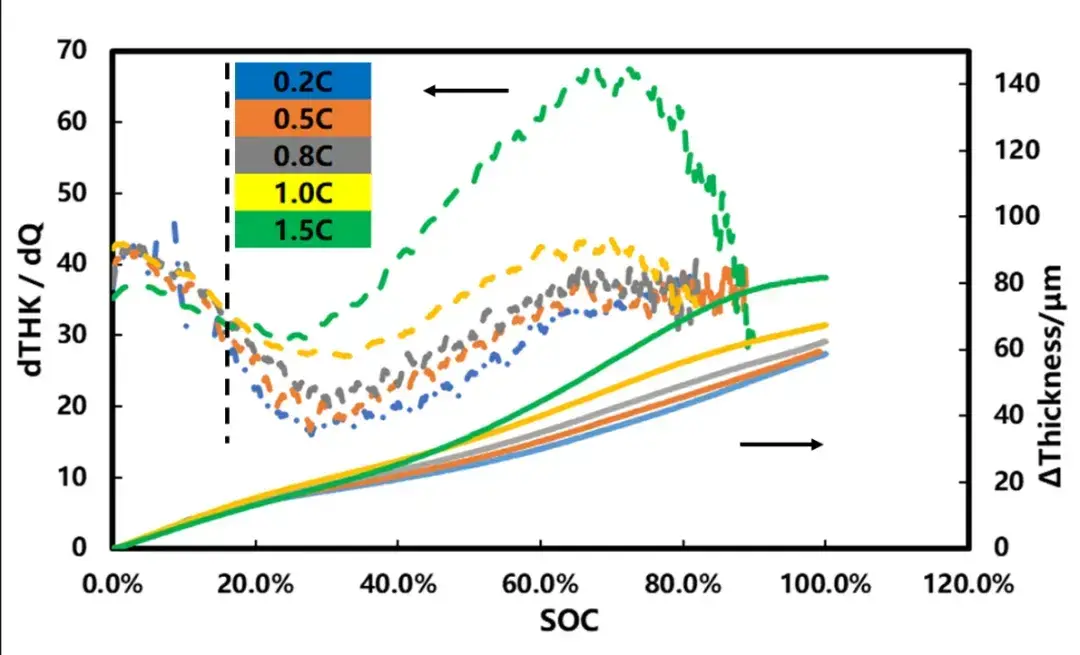

The differential capacity curves for different temperatures were further analyzed, as shown in Figure 4. As can be seen from the figure, the peak position of the differential capacity curve corresponding to 0.2C, 0.5C and 0.8C is synchronized with the change of the thickness swelling rate, indicating that the thickness change of the cell charging process is caused by the phase change of the positive and negative electrode material. With the doubling rate, the phase change peak moves to the right, indicating that the polarization is increasing. The slope of the differential capacity capacity curve is obviously different from others.

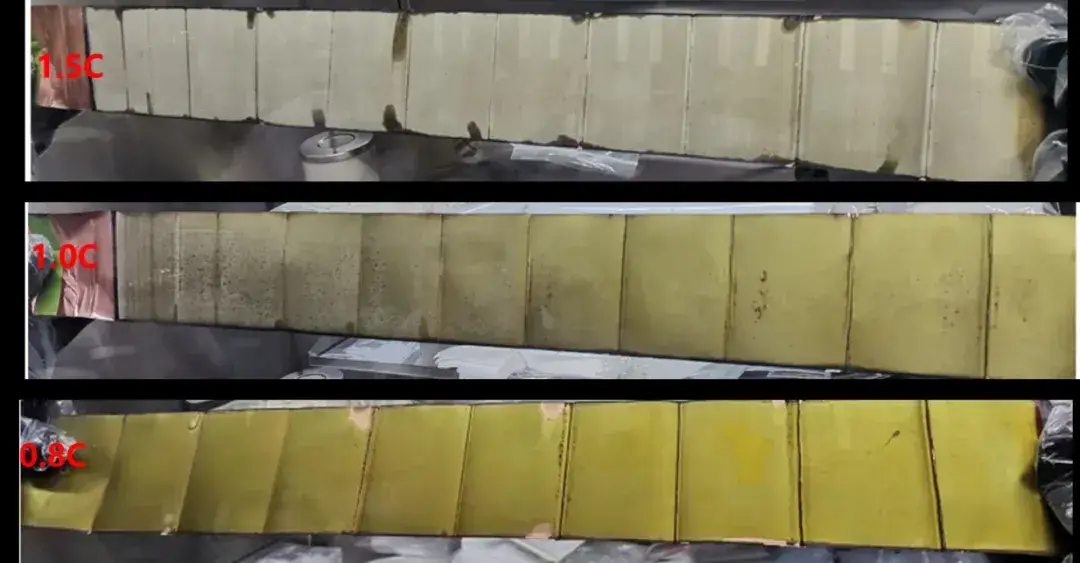

As shown in Figure 5, it is also obvious that the 1.0C and 1.5C x thickness swelling curves begin to separate from the other trix thickness swelling curves when the SOC is about 15%. This is likely because as the test ratio increases, the cell polarization increases, and there is lithium plating on the negative surface, which leads to the acceleration of the thickness swelling. To verify whether the pouch cell has lithium plating, observe negative surface color after disassembly, the figure 6. 1.5C rate full charge, pole surface all gray white, 1.0C times full charge, pole surface part gray white, indicating that both have different degrees of lithium plating, and 0.8C rate under filling negative pole is golden yellow, no lithium phenomenon, this is consistent with our conclusion from the thickness swelling curve.

Figure 4. Change curve of differential capacity and thickness of cell charging

Figure 5. Cell thickness swelling curve and differential curve

5.3 Post-mortem Validation

To confirm plating, cells were disassembled after full charge at each rate and the anode surfaces inspected visually:

-

1.5C full charge: anode surfaces were uniformly gray-white, indicating pervasive metallic Li deposition.

-

1.0C full charge: partial gray-white regions were observed—consistent with localized/light plating.

-

≤0.8C full charge: anode surfaces remained gold/yellow (typical of healthy graphite) with no visible plating.

These observations validate that the abnormal thickness signals correspond to real Li metal deposition and that the in-situ expansion method reliably detects plating onset and severity.

Figure 6. Full charge and disassembly picture of the electric cell

5.4 Stepwise Charge Experiment: Pinpointing the Onset SOC of Lithium Plating

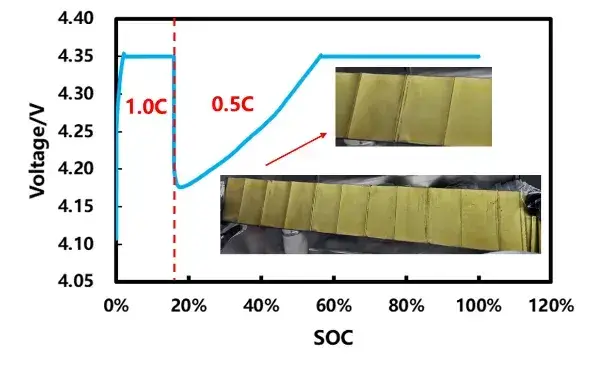

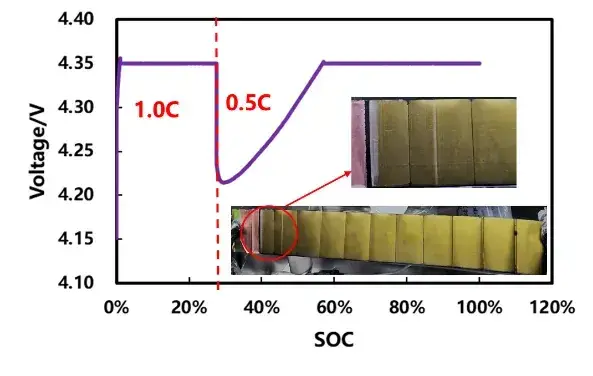

Two staircase experiments probed the precise SOC where plating begins during 1.0C charging:

-

Experiment A: 1.0C to ≈15.7% SOC, then switch to 0.5C to finish charge — post-mortem anode showed no plating.

-

Experiment B: 1.0C to ≈27.4% SOC, then switch to 0.5C — post-mortem anode showed light plating.

Thus, for this cell at 5°C, the plating onset under 1.0C lies between ~15.7% and ~27.4% SOC, matching the SOC range where thickness-vs-SOC curves began to separate. This result demonstrates the method’s ability to resolve an SOC window for plating onset rather than only identifying full-charge results.

|

|

Figure 7. Cell ladder ratio charging curve and disassembly picture

6. Summary

This study successfully employed an In-situ Thickness Swelling Analyzer (SWE) to investigate the expansion behavior of an LCO/graphite pouch cell under various charging C-rates at a low temperature of 5°C. By analyzing the rate of thickness change, we determined that constant-current charging above 1.0C induces lithium plating in this specific cell. The plating window was precisely identified as starting at approximately 15% SOC when charging at 1.0C.

Quantifying the precise C-rate, voltage, and SOC window for lithium plating provides invaluable data for battery developers. This methodology empowers the creation of sophisticated fast-charging strategies that maximize speed while ensuring safety and preventing degradation associated with lithium plating.

7. References

[1]. Thomas Waldmann, Björn-Ingo Hogg, Margret Wohlfahrt-Mehrens.Li plating as unwanted side reaction in commercial Li-ion cells -A review.Journal of Power Sources 384 (2018) 107–124.

[2]. Anna Tomaszewska, Zhengyu Chu, Xuning Feng, et al.Lithium-ion battery fast charging: A review.eTransportation 1 (2019) 100011.

Contact Us

If you are interested in our products and want to know more details, please leave a message here, we will reply you as soon as we can.