-

iestinstrument

An In-Depth Analysis of All-Solid-State Battery Research and Testing — Current Status and Practical Testing Guide

1. Abstract

All-solid-state batteries (ASSBs) promise higher intrinsic safety and the potential for much higher energy density by replacing flammable liquid electrolytes with solid ionic conductors. However, numerous materials and engineering challenges remain—chief among them ion conductivity, solid–solid interfacial contact, interfacial chemistry, and uneven lithium deposition. This article summarizes the current state of ASSB research, compares major solid-electrolyte classes (polymer, oxide, sulfide and composite), and describes practical testing methods and apparatus used to evaluate electrolyte and cell performance, with emphasis on quantitative metrics relevant to R&D and scale-up.

2. Introduction: The Imperative for All-Solid-State Batteries Technology

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have emerged as the cornerstone of electrochemical energy storage, prized for their high energy density, long cycle life, low self-discharge, and absence of memory effect. Their applications have rapidly expanded from portable electronics to electric vehicles (EVs), residential, and grid-scale storage, permeating modern society. This expansion, however, places unprecedented demands on battery safety and energy density.

Conventional LIBs rely on flammable, volatile organic liquid electrolytes. This inherent characteristic poses significant safety risks—including thermal runaway, fire, and explosion—under conditions like overheating, short-circuiting, overcharging, or mechanical damage. While innovations in battery pack design have somewhat mitigated these risks, the fundamental solution lies in evolving from structural to material-level innovation.

Furthermore, energy density remains a critical performance metric. Strategic national plans, such as “Made in China 2025” and the “New Energy Vehicle Industry Development Plan (2021-2035),” target cell-level energy densities of 400-500 Wh/kg by 2025 and 2030, respectively. Conventional liquid LIBs, constrained by their chemistry, are projected to hit a ceiling around 300 Wh/kg, falling short of future needs.

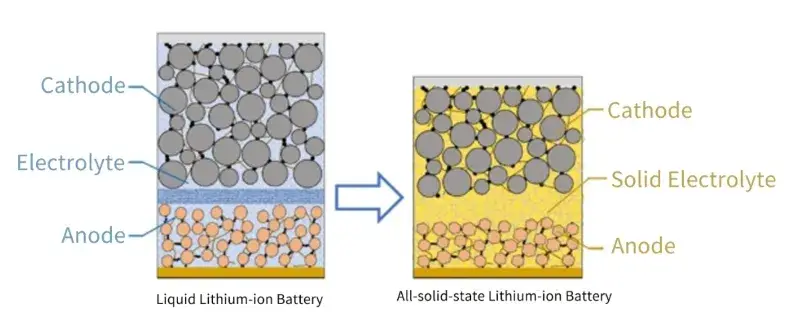

Consequently, developing safer, higher-energy-density storage technologies is paramount. Replacing liquid electrolytes with solid counterparts to create all-solid-state batteries (ASSBs) presents the most promising path forward. As illustrated in Figure 1, ASSBs share a similar operating principle with liquid LIBs. However, solid electrolytes offer superior thermal and chemical stability, eliminating leakage, combustion, or explosion risks and enhancing intrinsic safety. Their high Young’s modulus can effectively suppress lithium dendrite growth, potentially enabling the use of lithium metal anodes for a dramatic boost in energy density. Additionally, simplified packaging, the application of bipolar stacking to reduce inert components, and the potential elimination of complex cooling systems can further improve volumetric and gravimetric energy density at the system level.

d leads, and the battery module does not require a cooling system, which is expected to further improve the volume and mass energy density of the system.

Figure 1. Comparison of the structure of liquid lithium-ion batteries and all solid-state lithium-ion batteries

3. The Core Component: Current Status of Solid Electrolyte Research

Solid electrolytes, or fast ion conductors, are the heart of ASSBs. These materials are solid within the operational temperature range, exhibit excellent electronic insulation, and provide high ionic conductivity. They functionally replace both the liquid electrolyte and separator in conventional batteries, serving as the medium for lithium-ion transport.

Research has yielded diverse solid electrolytes, broadly classified into polymer-based, inorganic, and organic/inorganic composite types, with inorganic electrolytes further divided into oxides and sulfides.

3.1 Polymer-Based Solid Electrolytes

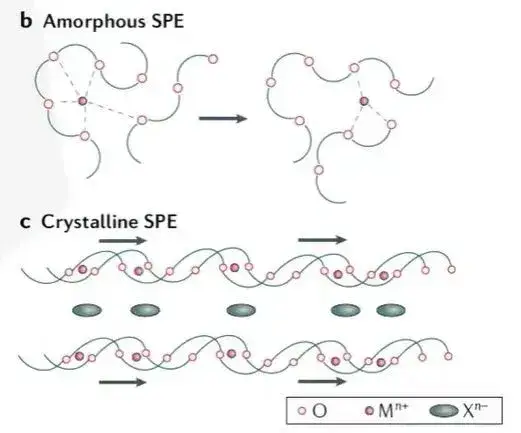

Typically formed by homogenously blending a polymer matrix with lithium salts, polymer solid electrolytes (SPEs) offer advantages like good flexibility, high adhesion, low cost, and ease of processing. Polar groups within the polymer (e.g., C=O, C=N, -O-, -S-) coordinate with lithium ions, facilitating salt dissociation and ion mobility. As shown in Figure 2, ion transport predominantly occurs in the amorphous regions above the glass transition temperature (Tg), relying on local segmental motion of polymer chains to create free volume for Li+ hopping.

A major limitation is their low room-temperature ionic conductivity (e.g., ~10^-7 to 10^-5 S/cm for PEO), insufficient for practical ASSBs. Common strategies to enhance conductivity include adding plasticizers to increase free volume or incorporating organic solvents to improve salt dissociation.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of the ion transport mechanism of polymer solid electrolyte

Polymer solid electrolytes usually have low room temperature ionic conductivity. For example, the ionic conductivity of PEO is in the range of 10-7~10-5 S/cm, which is difficult to meet the actual use needs of all-solid-state batteries. To improve the ionic conductivity of polymer electrolytes, common methods include adding plasticizers to increase the free volume between segments or adding organic solvents to further promote the dissolution of lithium salts.

3.2 Inorganic Solid Electrolyte

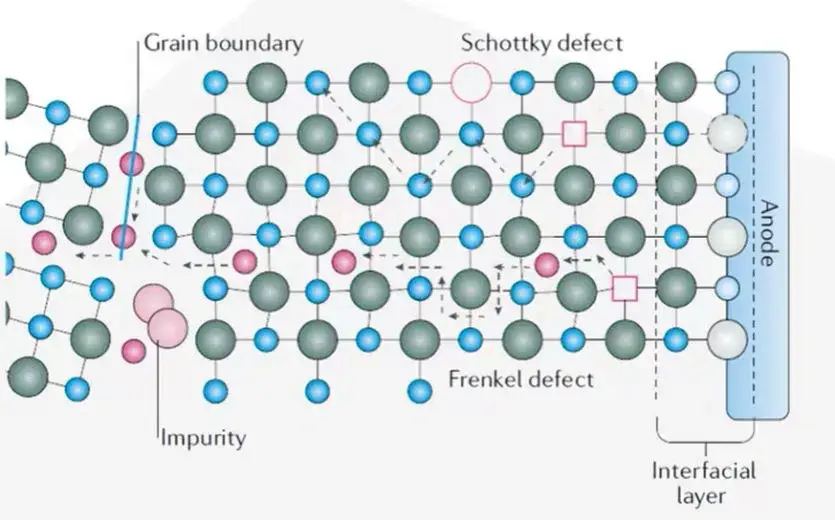

Ion migration in crystalline materials generally follows the Arrhenius law, depending on defect concentration and distribution within the crystal lattice. Mechanisms, illustrated in Figure 3, include vacancy diffusion, interstitial mechanisms, and coupled exchange processes.

Figure 3. Schematic diagram of the ion transport mechanism of crystalline solid electrolyte

3.2.1 Oxide Solid Electrolytes

Major types include perovskite-type (e.g., Li₃La₃Ti₂O₁₂, LLTO), garnet-type (e.g., Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂, LLZO), LISICON-type, and NASICON-type (e.g., Li₁.₅Al₀.₅Ge₁.₅(PO₄)₃, LAGP; Li₁.₃Al₀.₃Ti₁.₇(PO₄)₃, LATP) electrolytes. Their room-temperature conductivity typically ranges from 10^-4 to 10^-3 S/cm, improvable via elemental doping or optimized synthesis. For instance, Ta, Al, or Ca doping in LLZO can increase Li vacancy sites, boosting conductivity to ~10^-3 S/cm.

However, challenges persist. LATP and LAGP can be reduced by Li metal anodes due to their Ti⁴⁺ and Ge⁴⁺ content, forming mixed ionic/electronic conductive interphases. LLZO, while theoretically stable, reacts with atmospheric H₂O and CO₂, forming a detrimental Li₂CO₃ surface layer that harms conductivity and interfacial wettability. Their high Young’s modulus, while dendrite-suppressing, leads to poor physical contact with electrodes and an inability to accommodate volume changes during cycling, causing contact loss and mechanical failure. Their brittleness and the need for high-temperature sintering in ceramic/electrode fabrication pose significant processing challenges. Strategies like introducing polymer interlayers or developing composite electrolytes are being pursued to overcome these issues.

3.2.2 Sulfide Solid Electrolyte

Compared with oxide solid electrolytes, sulfide ions have a larger radius and smaller electronegativity than cations, so sulfide solid electrolytes have a lower binding force to lithium ions. This makes the ion transport channel formed in the sulfide wider than the oxide electrolyte and transports lithium ions more easily, thus showing higher ionic conductivity. In addition, sulfide solid electrolytes also have the advantages of excellent thermal stability and good mechanical properties. Based on composition and structure, sulfide solid electrolytes are mainly divided into glassy, Thio-LISICON, glass-ceramic, lithium sulfide silver germanium ore type, and LGPS superionic conductors. Glassy sulfide solid electrolytes include Li2S-GeS2、Li2S-SiS2、Li2S-P2S5-LiI, and their room temperature lithium ion conductivity is ~10-4 S/cm. Thio-LISICON type Li3.25Ge0.25P0.7S4 room temperature lithium-ion conductivity is 2.2×10-3 S/cm. Glass-ceramic Li7P3S11 room temperature lithium-ion conductivity is 2.2×10-3 S/cm. The lithium sulfide-silvergermanium sulfide electrolyte Li6PS5X (X=Cl, Br, I) has high lithium-ion conductivity, and the room temperature conductivity of Li6PS5Cl synthesized by the solid-phase method is as high as 4.96×10-3 S/cm. The superionic conductor Li10GeP2S12 (LGPS) is considered a milestone, with a room temperature lithium-ion conductivity of 1.2×10-2 S/cm, which is comparable to liquid electrolytes. After halogen doping, the room temperature lithium-ion conductivity of Li9.54Si1.74P1.44S11.7Cl0.3 superionic conductor even exceeds that of liquid electrolyte, reaching 2.5×10-2 S/cm.

In addition to high ionic conductivity, the unique mechanical properties of sulfide electrolytes are also one of the reasons why they are so popular. The modulus of sulfide electrolytes is between that of oxides and polymers. From the perspective of material mechanics, sulfide electrolytes can not only inhibit the growth of lithium dendrites, at the same time, its texture is soft and can be densified through simple cold pressing, avoiding the high-temperature sintering process similar to oxide ceramics. However, sulfide electrolytes have low fracture toughness values and are prone to brittle fracture during battery preparation and cycling, causing mechanical failure of the battery.

Most sulfide solid electrolytes are unstable in the air. A small amount of moisture in the air can cause hydrolysis of the electrolyte, leading to irreversible structural changes and reduced ionic conductivity, as well as the production of toxic H2S gas. Therefore, the synthesis, storage and processing of sulfide electrolytes require strict anhydrous conditions to maintain the stability and safety of the material structure. This obviously increases the complexity and cost of the production process and limits its large-scale production and application. Based on the soft and hard acid-base theory, researchers are currently developing air-stable sulfide electrolytes through oxide blending or element doping.

3.3 Organic/Inorganic Composite Solid Electrolytes

Currently, single inorganic solid electrolytes and polymer solid electrolytes have various problems such as low ionic conductivity, dendrite generation, and unstable interfaces, respectively, and cannot meet the performance requirements of all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. To overcome the shortcomings of inorganic solid electrolytes and polymer electrolytes, inorganic fillers are added to the polymer matrix to form organic/inorganic composite solid electrolytes, it can not only improve the ionic conductivity of polymer solid electrolytes, but also inhibit dendrite generation, improve mechanical strength, improve interface stability and compatibility, etc.

Composite solid electrolytes combine the advantages of inorganic solid electrolytes and organic solid electrolytes. The solid electrolyte obtained by adding inorganic fillers to the polymer solid electrolyte has excellent comprehensive properties, inorganic fillers can play three roles:

- Reduce crystallinity and increase the amorphous phase area, which facilitates Li+ migration;

- Fast Li+ channels can be formed near filler particles;

- Increase the mechanical properties of the polymer matrix, making it easier to form films .

Organic-inorganic composite electrolytes can improve lithium-ion conductivity. There are three main lithium ion conduction mechanisms:

- The organic phase conducts lithium ions;

- The inorganic phase conducts lithium ions;

- The organic-inorganic interface conducts lithium ions.

4. Key Challenges in All-Solid-State Batteries Development

4.1 Low Ionic Conductivity

The feasibility of ASSBs first hinges on the solid electrolyte’s ionic conductivity. While liquid electrolytes offer ~10^-2 S/cm, oxide ceramics achieve only ~10^-4 S/cm, and their cold-pressed powders are as low as ~10^-8 S/cm. Polymer SPEs reach only ~10^-6 to 10^-5 S/cm at room temperature, requiring operation at elevated temperatures (~60°C) where they approach a molten state. Sulfide solid electrolytes, with conductivities rivaling liquids, and composite electrolytes are therefore the primary candidates for practical ASSBs from a conductivity standpoint.

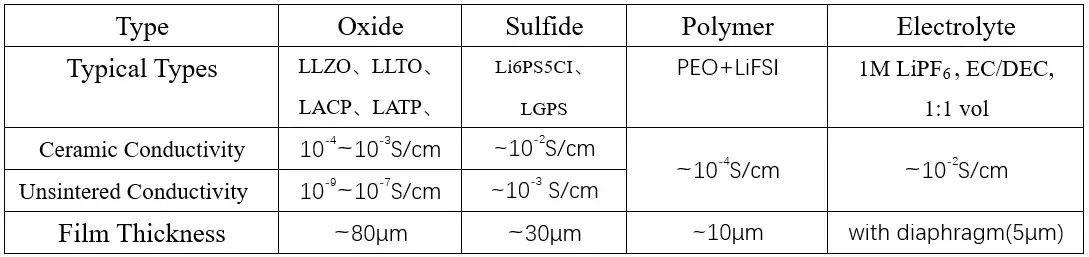

Table 1. Comparison of Three Common Solid Electrolytes and Liquid Electrolytes

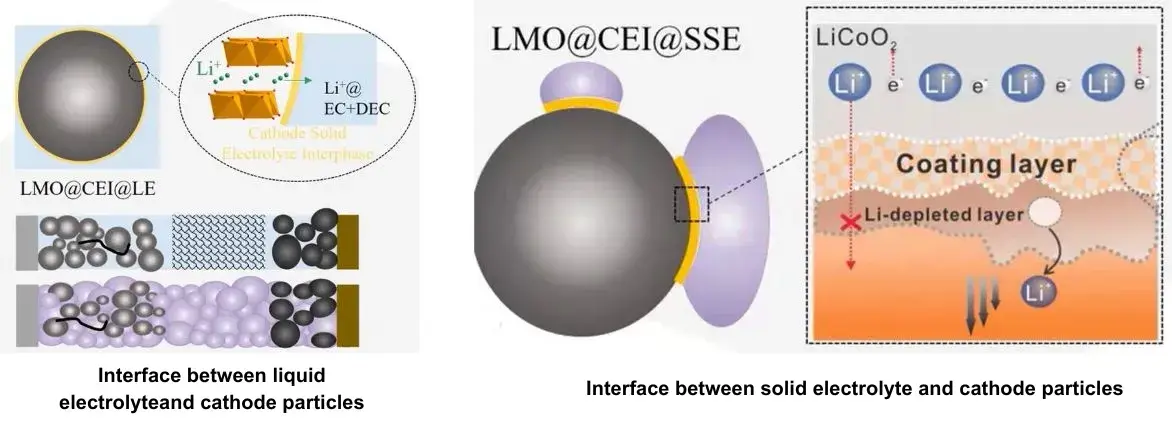

4.2 Poor Solid-Solid Physical Contact

In liquid LIBs, the fluid electrolyte fully infiltrates electrode pores, forming an excellent liquid-solid interface for efficient ion transport (Figure 4). In ASSBs, the immobile solid electrolyte results in poor solid-solid contact with electrode particles, leading to high interfacial resistance and limited active contact area. Mitigation strategies include in-situ growth of solid electrolytes on electrode materials to coat particles and using hot/cold pressing to reduce porosity. However, compensating for poor contact often requires incorporating a high volume fraction (~25% or more) of solid electrolyte into the electrodes, which dilutes active material content and reduces both gravimetric and volumetric energy density.

Figure 4. Comparison of the interface between liquid electrolyte and solid electrolyte and cathode particles

To overcome the problems caused by solid-solid physical contact in all-solid-state batteries, researchers improved the solid-solid interface by growing solid electrolytes in situ on the electrode materials, this coating layer effectively improves the solid-solid physical contact inside the electrode and reduces the interface impedance. In addition, reducing the porosity inside the electrode through hot or cold pressing processes is also a simple and effective strategy to improve the physical contact between electrode components.

In addition, considering that the lithium-ion conductivity and interfacial infiltration of the solid electrolyte are not as good as those of the liquid electrolyte, it is necessary to increase the volume percentage of the solid electrolyte in the positive and negative active material materials to ensure the lithium-ion conductivity of the positive and negative electrode sheets. Currently, in sulfide all-solid-state batteries, more than 25% solid electrolyte needs to be added to the positive and negative electrodes to ensure certain electrical performance. Adding a large amount of solid electrolyte to the electrode reduces the proportion of active material and the mass capacity density of the battery; on the other hand, it increases the volume of the electrode and reduces the volume capacity density of the battery. At the same time, the electronic conductivity of the solid electrolyte itself is very low. Without adding an electronic conductive agent, increasing the volume percentage of the solid electrolyte will lead to a decrease in the electronic conductivity of the electrode, affecting the battery rate performance.

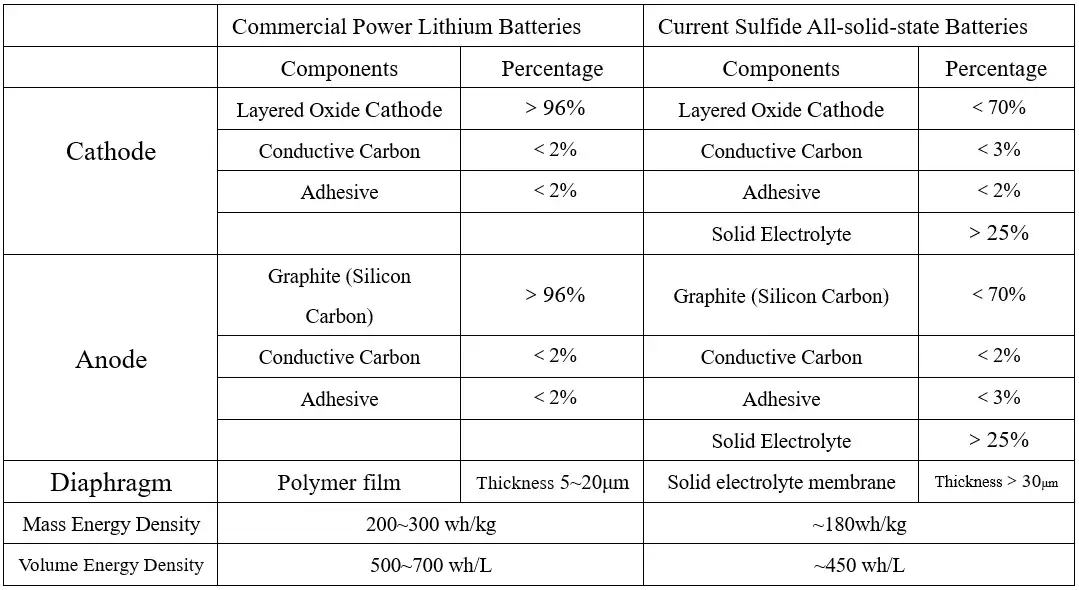

Table 2. Comparison of Parameters Between Commercial Lithium-ion Batteries and Current Sulfide All-Solid-state Batteries

4.3 Interfacial Chemical/Electrochemical Side Reactions

The ion conduction at the contact interface between solid electrolyte and electrode is mainly affected by the chemical/electrochemical compatibility of the interface, which is mainly reflected in the diffusion of interface elements, interface electrochemical side reactions and space charge layer. The (electro)chemical incompatibility between the sulfide electrolyte and the electrode material causes irreversible parasitic reactions at the interface, forming a complex interface phase with high electronic conductivity and low ion conductivity, further hindering the rapid transport of ions at the interface. In addition, the difference in lithium chemical potential between the sulfide electrolyte and the layered cathode material may lead to the formation of an interface space charge layer and also hinder the migration of lithium ions at the interface.

To improve the interface compatibility between the solid electrolyte and the cathode material and suppress the occurrence of interface (electro)chemical side reactions, the most used and effective method at present is to cover the surface of the cathode material to build an interface protective layer. The cathode material coating in all-solid-state batteries is usually a fast ion conductor. These coating materials are required to have high electrochemical stability, high ionic conductivity and electronic insulation, aiming to suppress interface side reactions while not hindering the transport of lithium ions across the interface. Among them, LiNbO3 is favored due to its relatively high ionic conductivity (~10-6 S/cm) and high electrochemical stability with sulfide and cathode materials, and is currently the most widely used coating material.

4.4 Inhomogeneous Lithium Deposition/Stripping

Uneven Li plating/stripping at the Li metal/electrolyte interface leads to dendrite nucleation and growth, risking short circuits. This problem is coupled with interfacial contact and stability issues. Applying appropriate stack pressure during cycling can improve contact and promote Li creep. Since grain boundaries often have lower shear modulus, enhancing the density of the solid electrolyte layer and ensuring uniform interfacial contact are crucial for dendrite suppression.

5. A Testing Paradigm for Solid-State Battery Materials

5.1 A comprehensive electrochemical performance testing method for solid electrolytes

The solid electrolyte testing system SEMS1100 (jointly developed by IEST Instrument and Xiamen University) is a multi-functional testing system dedicated to solid electrolyte samples. It is a fully automatic measurement equipment for the electrochemical properties of solid electrolytes that integrates tableting, testing and calculation. The system adopts an integrated structural design, including a pressurization module, an electrochemical test module, a density measurement module, a ceramic sheet pressing and clamping module, etc. It is suitable for testing various types of oxides, sulfides, polymers and other solid electrolytes.

Figure 5. Schematic of solid electrolyte testing equipment

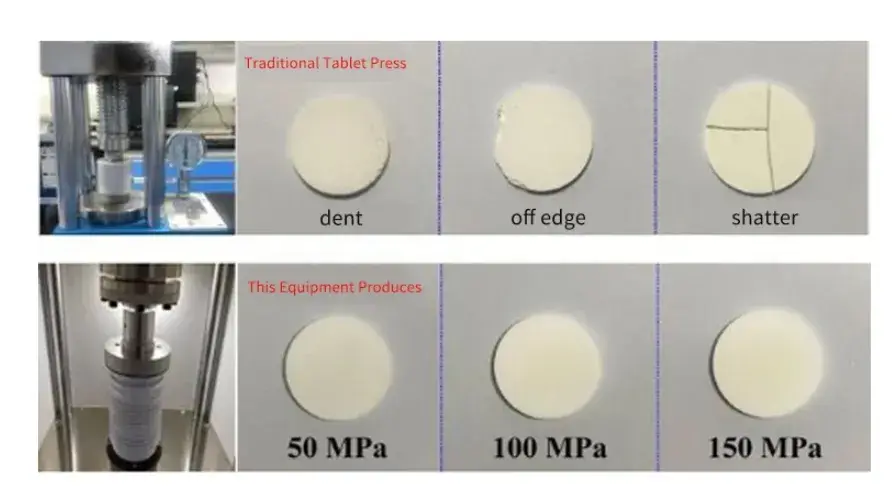

5.2 Powder Tablets

At present, when evaluating the electrochemical performance of solid electrolyte powder, it is usually necessary to press the powder into tablets, and samples with poor interface contact also need to spray conductive metal on the surface as an ion blocking electrode. The size and uniformity of the force applied during tableting will greatly affect the integrity of the prepared ceramic tablets. Figure 6 shows macro photos of ceramic tablets obtained by different tableting equipment, among them, the uniform pressure of SEMS1100 equipment is used to prepare solid electrolyte ceramic sheets, which can ensure complete and uniform samples in different pressure ranges, reduce the risk of sample damage, and improve yield and testing efficiency.

Figure 6. Comparison of production results of different equipment

5.3 Ionic Conductivity Measurement

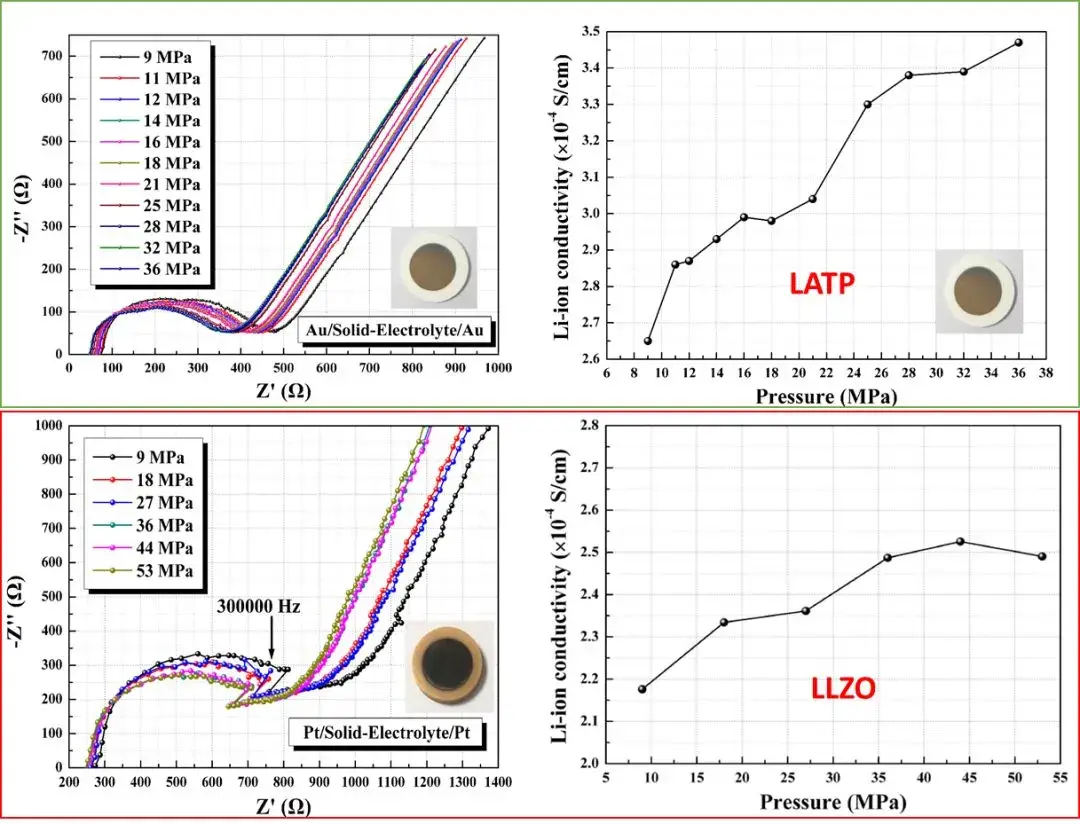

SEMS1100 was used to conduct electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and ionic conductivity tests on two different solid electrolyte materials, Li1.3Al0.3Ti1.7(PO4)3 (LATP) and Li6.5La3Zr1.5Ta0.5O12 (LLZO). As shown in Figure 7, by applying different quantitative pressures to the sandwich ceramic piece and measuring its electrochemical impedance spectrum, it was found that the test pressure will affect its ionic conductivity to varying degrees, this shows that it is necessary to test the electrochemical performance of solid electrolytes by applying stable and quantified pressure.

Figure 7. Electrochemical impedance spectra of two solid-state electrolytes and their ionic conductivity changes with pressure.

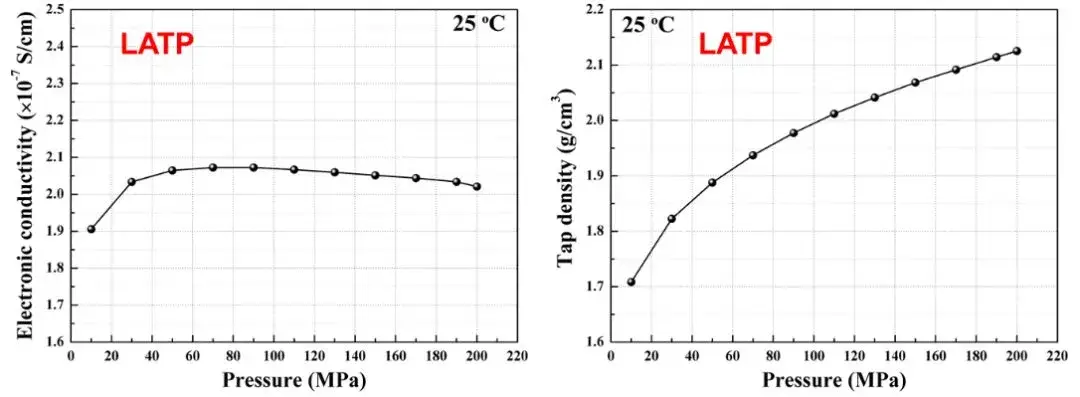

5.4 Synchronous Electronic Conductivity & Compaction Density Testing

Through the SEMS1100 equipment, the electronic conductivity and compaction density of LATP powder can be simultaneously tested during the tableting process. As shown in Figure 8, as the applied pressure increases, the compacted density increases from the initial 1.7g/cm3 to 2.1g/cm3, the electronic conductivity reaches stability around 50MPa, that is, the density and electronic conductivity trends of the solid electrolyte material are not completely consistent. This shows that under different pressure conditions, different characteristic indicators of solid electrolytes need to be tested simultaneously to obtain comprehensive and accurate measurement results.

Figure 8. Changes in electronic conductivity and compacted density of LATP solid electrolyte to pressure

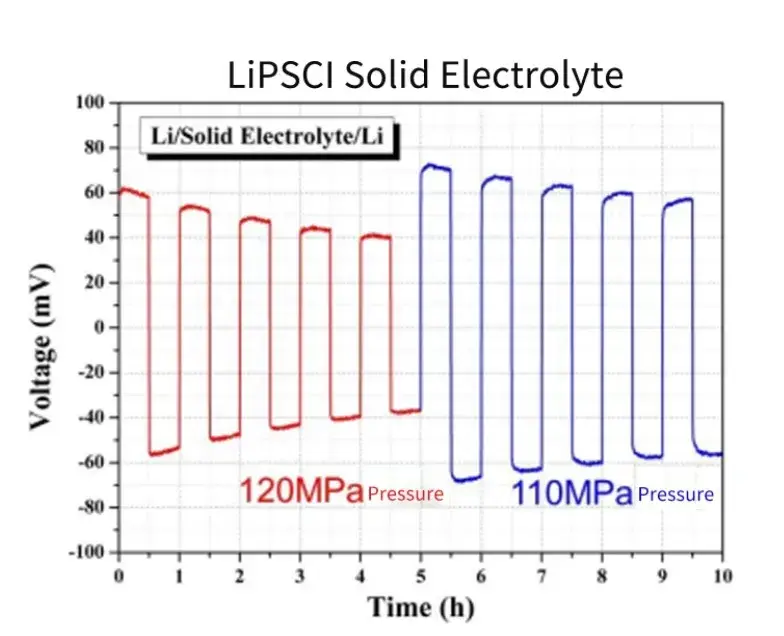

5.5 Cycling Performance in Symmetric Li Metal Cells

Assemble the Li-SE-Li symmetrical battery in the sealed fixture provided by SEMS1100, apply different pressures to the battery, conduct cyclic deposition tests of lithium metal, and measure the potential changes of the symmetrical battery. As shown in Figure 9, when the applied pressure is reduced from 120MPa to 110MPa, the overpotential of the battery increases significantly, this shows that the deposition behavior of lithium metal batteries is relatively sensitive to pressure changes, and it is of great significance to evaluate the interfacial stability of solid electrolytes by changing the applied pressure.

Figure 9. Cyclic charge-discharge test of symmetrical battery

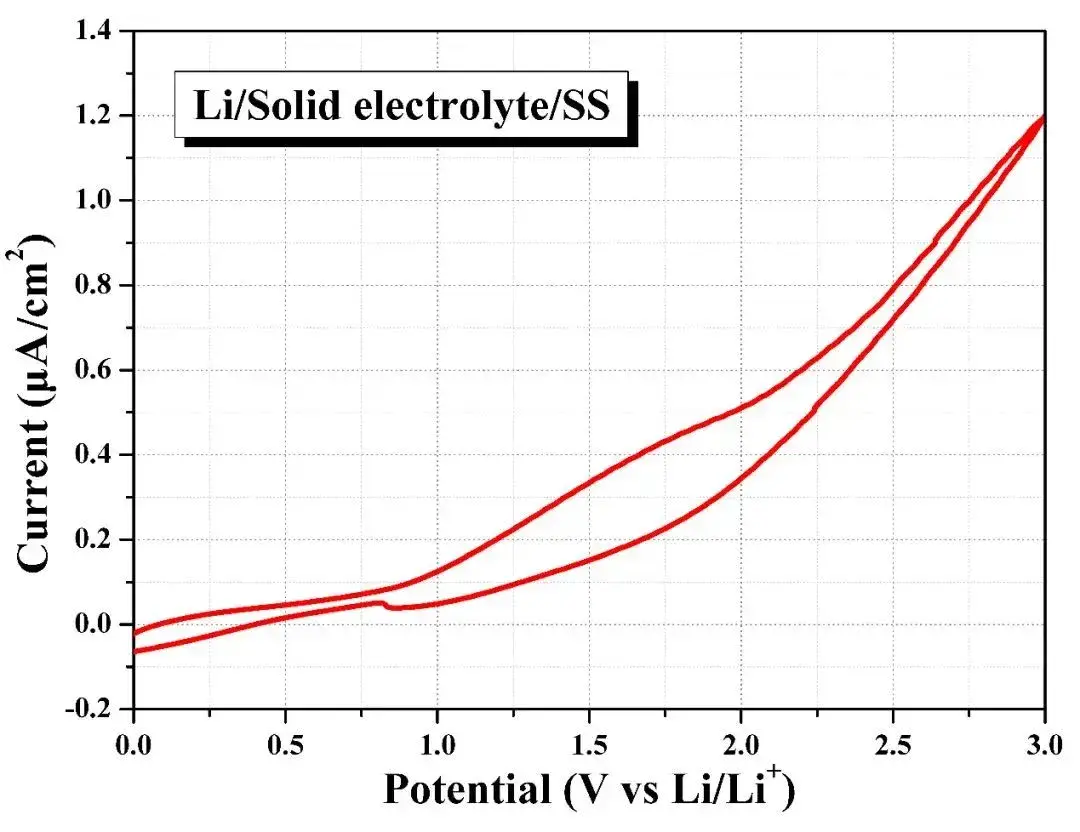

5.6 Electrochemical Stability Window Determination

Assemble the Li-SE-stainless steel battery in the sealed fixture provided by SEMS1100 and conduct cyclic voltammetry to test its redox potential. As shown in Figure 10, when the overpotential increases to 3V, the oxidation current density of the battery is only about 1.2μA/cm2, this shows that the solid electrolyte is relatively stable within the voltage window of 0~3V, that is, the SEMS1100 equipment can realize pressurized and sealed electrochemical tests of different solid electrolyte materials and their lithium metal batteries.

Figure 10. Electrochemical window testing of solid electrolytes

6. Summary of All-Solid-state Batteries Research

-

The low ionic conductivity of oxide and polymer solid electrolytes limits their use in practical ASSBs, directing focus toward sulfide-based and composite electrolytes.

-

For sulfide electrolytes to achieve commercialization, their air instability and associated high processing costs must be resolved.

-

Replacing liquid electrolytes introduces challenges like inferior ionic percolation networks in electrodes, poor solid-solid contact, and reduced energy density, which require innovative electrode design.

-

Despite the high research complexity, the profound potential safety and energy density advantages of ASSBs warrant continued and intensive investigation.

- Robust solid-state battery testing—including pressure-resolved conductivity, symmetric Li cycling, and hermetic EIS—is essential to compare materials fairly and to accelerate translation from lab to manufacturing.

7. References

[1] Liang Yuhao. Research on interface regulation of sulfide-based all-solid-state batteries [D]. Beijing: University of Science and Technology Beijing, 2023.

[2] FanL-Z, He H, Nan C-W. Tailoring inorganic-polymer composites for the mass production of solid-state batteries[J]. Nature Review Materials, 2021, 6(11):1003-1019.

[3] Meyer W H. Polymer electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries[J]. Advanced Materials,1998,10(6): 439-448.

[4] Allen J L, Wolfenstine J,Rangasamy E,et al . Effect of substitution (Ta, Al, Ga) on the conductivity of Li7La3Zr2O12[J]. Journal of Power Sources,2012,206(15): 315-319.

[5] Zhu Y, Mo Y. Material design principles for air-stable lithium/sodium solid electrolytes[J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition,2020,59(40): 17472-17476.

Contact Us

If you are interested in our products and want to know more details, please leave a message here, we will reply you as soon as we can.