-

iestinstrument

Analysis of Argyrodite Solid Electrolyte Degradation Using High-Frequency EIS

1. Abstract

Sulfide-based solid electrolytes—in particular argyrodite solid electrolyte—offer high ionic conductivity, favorable mechanical properties, and good compatibility with various electrode active materials. However, even trace moisture in air can trigger reactions that produce H₂S and reduce Li⁺ conductivity, posing a major reliability concern for all-solid-state lithium batteries. This study uses high-frequency electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) up to 100 MHz to pinpoint where conductivity losses occur after brief air exposure and to quantify changes in bulk and grain-boundary ion transport. The measurements show that one-hour exposure to air at a dew point of −20 °C primarily increases grain-boundary impedance and its activation energy, while the internal bulk impedance remains effectively unchanged. These results demonstrate that high-frequency EIS can spatially resolve the early-stage moisture-induced degradation of argyrodite solid electrolytes.

2. Introduction: Argyrodite Solid Electrolyte and Moisture Sensitivity

Sulfide-based solid electrolyte materials such as argyrodite-type Li₇−xPS₆−xClx combine high room-temperature ionic conductivity with mechanical properties favorable for cell assembly. However, their sulfide chemistry reacts readily with even trace water, generating corrosive or toxic species (notably H₂S) and forming low-conductivity surface phases. Understanding whether conductivity losses originate in the particle bulk or at particle interfaces (grain boundaries) is essential for optimizing material handling and cell manufacturing.

3. Experimental: Sample preparation and high-frequency EIS setup

We examined commercially sourced argyrodite Li₇−xPS₆−xClx (LPSCl, x ≈ 1, D₅₀ ≈ 3.5 μm, Mitsui Mining & Smelting, Japan). Powder samples (50 mg) were pressed in a 7 mm inner-diameter zirconia die at 200 MPa to form pellets (typical thickness ~0.9 ± 0.01 mm). Two sample states were defined: a reference (Ref.SE) measured prior to air exposure, and an exposed sample (Exposed SE) after 1 h exposure to flowing air (dew point −20 °C, flow 0.8 L·min⁻¹). EIS spectra were collected between 100 MHz and 20 Hz over the temperature range 180–298 K using an EIS system equipped with a temperature control module (4990EDMS120K, Lakeshore 33x, TOYOTech, Japan). Normalized impedance Z (Ω·cm) was calculated as Z = (Z_m × S) / d, where S is pellet area (7 mm diameter) and d the pellet thickness. A custom sealed die and a powder resistivity and compaction density tester(PRCD) (proprietary instrument from IEST) were used for pellet preparation and to enable in-situ tests under controlled compaction pressures up to 600 MPa.

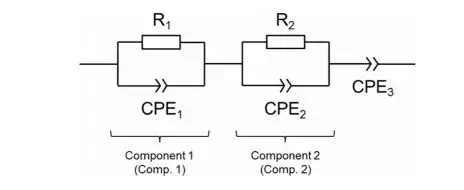

Figure 1. Equivalent circuit diagram fitted from the EIS data

4. Results and Discussion

4.1 Room Temperature Performance Degradation

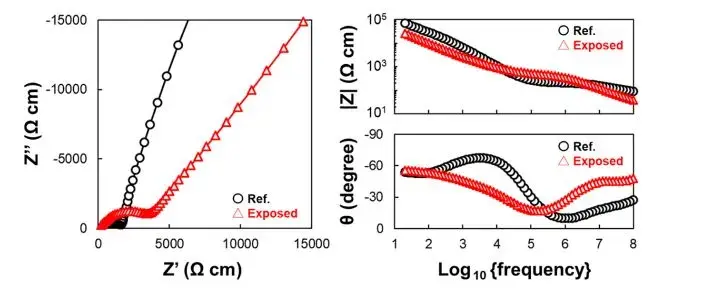

At 298 K, Nyquist and Bode spectra show that Exposed SE displays a substantially larger semicircle than Ref.SE, indicating a higher total ionic resistance after air exposure. Fitting the spectra returns room-temperature Li⁺ conductivities of approximately 0.70 mS·cm⁻¹ for Ref.SE and 0.28 mS·cm⁻¹ for Exposed SE — i.e., exposed samples retain only about 40% of the original conductivity. Because the absolute impedance values are small even at 100 MHz (due to inherently high conductivity), bulk and grain-boundary components are not clearly separated at 298 K, preventing a straightforward partitioning of the observed conductivity drop into bulk vs. interface contributions at room temperature.

Figure 2. Nyquist and Bode plots of the solid electrolyte before and after exposure to air

4.2 Low-temperature EIS: Separating bulk and grain-boundary components

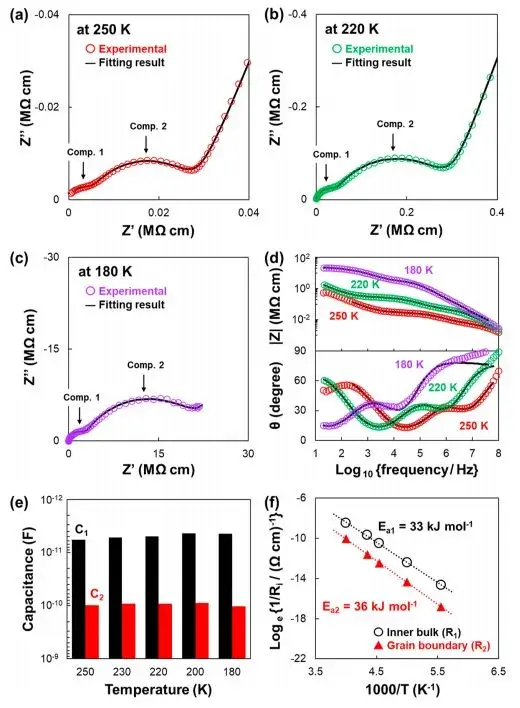

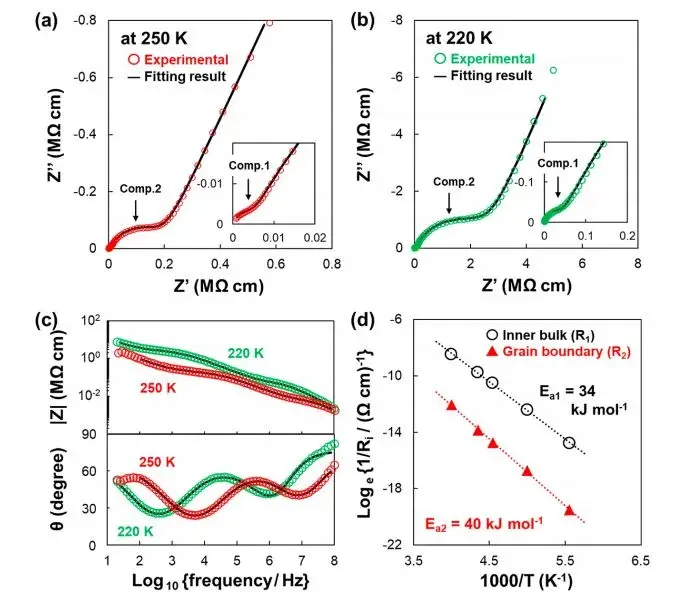

Therefore, to more accurately distinguish between the bulk impedance and grain boundary impedance components of the material, the authors conducted EIS measurements at lower temperatures on the sample not exposed to air (Ref.SE) and calculated its ionic conductivity activation energy. The test results are shown in Figure 3. Figures 3a-d depict Nyquist and Bode plots obtained for the samples before and after exposure to air at temperatures ranging from 180 to 250 K. In comparison to the spectra at 298 K (Figure 2), the Nyquist plots clearly show pseudo-capacitive components existing in the form of two semicircles representing different elements. Figure 3e summarizes the capacitance values C1 and C2 calculated from the equivalent circuit fitting at each temperature, revealing consistent values of approximately ~10−12 and ~10−11F for C1 and C2, respectively, which align with results reported in relevant literature. Specifically, the two parallel R-CPE components, R1-CPE1 and R2-CPE2, correspond to bulk impedance and grain boundary impedance of the material.

Figure 3 presents the Arrhenius plot of the ionic conductivity components at different temperatures. The linear fits yielded activation energies Ea1 and Ea2 for the bulk and grain boundary ionic conductivities, respectively, measured at 33 and 36 kJ*mol−1. Notably, the activation energy for ionic conductivity at the grain boundaries of the solid electrolyte interface is slightly higher. This is attributed to the presence of trace substances such as carbonates or adsorbed water on the particle surfaces, which have a certain impact on ion transport even in the absence of exposure to air.

Figure 3. EIS test results and Arrhenius plots for samples not exposed to air (Ref. SE)

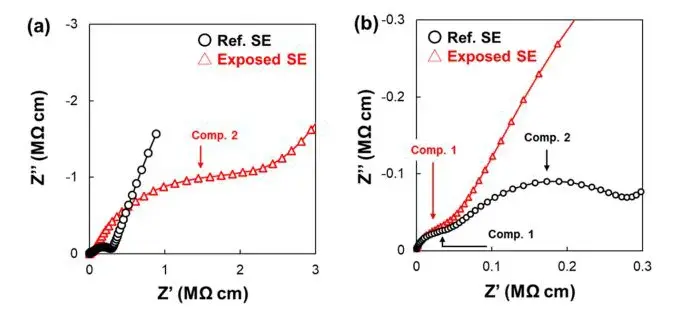

4.3 Effect of air exposure: Grain boundaries are the primary site of degradation

Equivalent low-temperature measurements on Exposed SE reveal a marked increase in the low-frequency R₂ (grain-boundary) contribution, while R₁ (bulk) and Ea₁ remain essentially unchanged. The Arrhenius behavior for the grain-boundary conductivity shifts to a higher activation energy after exposure, confirming that air exposure increases both resistance and the energy barrier for interparticle Li⁺ transport. Combining the 220 K Nyquist overlays for Ref.SE vs. Exposed SE makes this point explicit: the high-frequency (bulk) semicircle shows little change, whereas the low-frequency semicircle (grain boundary) grows substantially. The study therefore attributes most of the room-temperature conductivity loss to grain-boundary degradation rather than bulk decomposition.

Figure 4. Presents the EIS test results and Arrhenius plot for the sample exposed to air (Exposed SE).

4.4 Mechanistic interpretation: Surface hydrolysis and secondary phases

Surface analytical results reported by the authors indicate the formation of several decomposition products on particle surfaces after moisture exposure, including phosphate species (P–O), sulfate species (S–O), carbonate (CO₃²⁻), thiol groups (–SH), and hydrated surface phases. Because the ionic conductivity of these decomposition products is orders of magnitude lower than that of argyrodite LPSCl, their presence at particle boundaries effectively blocks Li⁺ pathways and increases grain-boundary impedance. The authors further note that initial degradation begins at particle surfaces and may subsequently propagate inward depending on exposure conditions. In addition, progressive hydrolysis can lead to formation of nanocrystalline secondary phases and novel interparticle interfaces that further complicate impedance signatures; however, EIS alone cannot unambiguously separate impedance arising from nanocrystals versus that from hydrated surface layers.

Figure 5. Nyquist plot and enlarged high-frequency region plot of the sample before and after exposure to air at 220 K.

4.5 Advantages of high-frequency (≤100 MHz) EIS for process control

Another possible reason for the increase in grain boundary impedance is the formation of new grain boundaries between the solid electrolyte and nanocrystals during further hydrolysis processes. However, it is challenging to distinguish between nano-crystal impedance and the impedance caused by surface hydrolysis solely through EIS testing. Despite these limitations, high-frequency EIS impedance spectroscopy measurements up to 100 MHz still contribute to identifying positions where the ion conductivity deteriorates due to exposure to air, which makes this measurement method a powerful tool for analyzing the effects of material modifications on sulfide-based solid electrolytes and optimizing the manufacturing processes of all-solid-state batteries.

5. Conclusion

This study successfully utilized high-frequency EIS (up to 100 MHz) to analyze an argyrodite solid electrolyte after exposure to a dry air atmosphere. This advanced technique effectively deconvoluted the overall impedance into bulk and grain boundary contributions, a task challenging for standard EIS equipment. The analysis demonstrated that the degradation in ionic conductivity after air exposure is predominantly due to a significant increase in grain boundary resistance and its associated activation energy. The bulk component of the electrolyte remained largely unaffected. This localized increase in impedance is consistent with surface hydrolysis and the formation of low-conductivity decomposition products on the sulfide-based solid electrolyte particles, while the bulk crystal structure remains intact. The methodology proves to be a powerful tool for pinpointing the location of ionic conductivity degradation and for optimizing the manufacturing processes of all-solid-state batteries.

6. References

Morino Y, Sano H, Kawaguchi S, et al. High-Frequency Impedance Spectroscopic Analysis of Argyrodite-Type Sulfide-Based Solid Electrolyte upon Air Exposure[J]. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 2023, 127(37): 18678-18683.

7. IEST Related Testing Equipment Recommendation

IEST has pioneered a multifunctional testing system specifically designed for solid electrolyte samples (SEMS), an automated device that integrates pressing, testing, and calculating the electrochemical performance of solid electrolytes. The system features an all-in-one design, including a pressing module, electrochemical testing module, density measurement module, and ceramic pressing and clamping module, making it suitable for in-situ testing of various electrolytes such as oxides, sulfides, and polymers.

Contact Us

If you are interested in our products and want to know more details, please leave a message here, we will reply you as soon as we can.