-

iestinstrument

Multi-physics Field Coupling Principle Of Lithium Plating In Pouch Cells

1. Abstract

Lithium plating (lithium dendrite formation) remains a principal failure mode in lithium-ion pouch cells, especially under fast charging, low temperature or when electrodes age. This article summarizes mechanisms of lithium plating, outlines nondestructive and destructive detection methods, and presents an in-situ thickness-expansion test protocol that identifies the SOC/voltage/temperature window where plating occurs. We then describe a phase-field / diffusion / electrostatic multiphysics model used to simulate dendrite morphology and estimate plated Li quantity from measured thickness changes. Finally, we compare graphite lithiation (intercalation) versus metallic lithium deposition in terms of volume change and show how in-situ expansion monitoring can provide a sensitive early indicator of lithium dendrite growth

2 . Lithium Plating Phenomenon

Lithium plating in lithium-ion batteries is a common failure mechanism. This phenomenon occurs when lithium ions cannot be intercalated into the anode material promptly—either due to insufficient accommodation sites or hindered ion transport—leading to their accumulation and subsequent reduction to metallic lithium. The primary causes of lithium plating can be categorized into five groups:

-

Anode aging and reduced lithium storage capacity — the anode can no longer accommodate the same lithium amount, so excess lithium plating.

-

Fast charging, overcharging, or low-temperature charging — elevated local overpotentials or slow kinetics favor surface reduction.

-

Abnormal lithium intercalation pathways — heterogeneity in electrode microstructure or SEI can block intercalation sites.

-

Irregularities in electrodes or separators — damaged electrodes, separators or local mechanical defects can trigger localized plating.

-

Localized / special-cause events — manufacturing defects or binder migration leading to fixed-location plating.

Plated lithium often forms lithium dendrites, which possess high reactivity and a large surface area. Their growth poses significant risks: (a) They can penetrate the separator, causing internal short circuits, potentially leading to thermal runaway; (b) During discharge, lithium dendrites may not fully re-dissolve, forming isolated “dead lithium” that depletes active lithium, reduces coulombic efficiency, and diminishes capacity; (c) Freshly deposited lithium reacts with the electrolyte, forming additional Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI), consuming electrolyte and increasing internal resistance, further degrading performance.

Understanding the root causes and boundary conditions for lithium plating is crucial for battery manufacturers and users. Consequently, effective detection and prevention strategies are key research priorities, which IEST aims to address.

3. Detection Methods

Common techniques for identifying lithium plating fall into three categories:

-

Monitoring Anode Potential vs. Li/Li+: Using a reference electrode or half-cell configuration, this method detects conditions where the anode potential drops below 0 V vs. Li/Li+, favoring lithium metal deposition over graphite intercalation, especially under low-temperature and/or high-current charging.

-

Analyzing Performance Degradation: Lithium plating accelerates cell aging. Techniques like electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (increased resistance), differential voltage analysis, or neutron diffraction detect these indirect electrical or compositional changes.

-

Post-Mortem Physical/Chemical Analysis: Direct examination of disassembled cells for metallic lithium.

Method (1) requires significant cell modification, and the reference electrode might interfere with cell processes. Method (2) tracks capacity fade related to active lithium loss, but distinguishing irreversible “dead lithium” from reversibly plated lithium—which can later intercalate or re-dissolve—is challenging. Overall, these methods often struggle to balance convenience, practicality, and cost-effectiveness.

IEST offers a simpler, faster approach for identifying the lithium plating window. Utilizing a thickness dilatometer with 0.1 µm resolution, we precisely measure cell thickness changes during cycling. By plotting thickness against State of Charge (SOC) under constant pressure or gap conditions, abnormal thickness increases clearly indicate lithium plating. This thickness-based metric provides a highly sensitive, rapid, and non-destructive detection method compared to capacity, impedance, or voltage-based analyses.

4. Lithium Expansion Experiment

This experiment employed an in-situ swelling analyzer (SWE) to quantitatively assess the voltage window for lithium plating at different temperatures, offering a new method for developing fast-charging protocols.

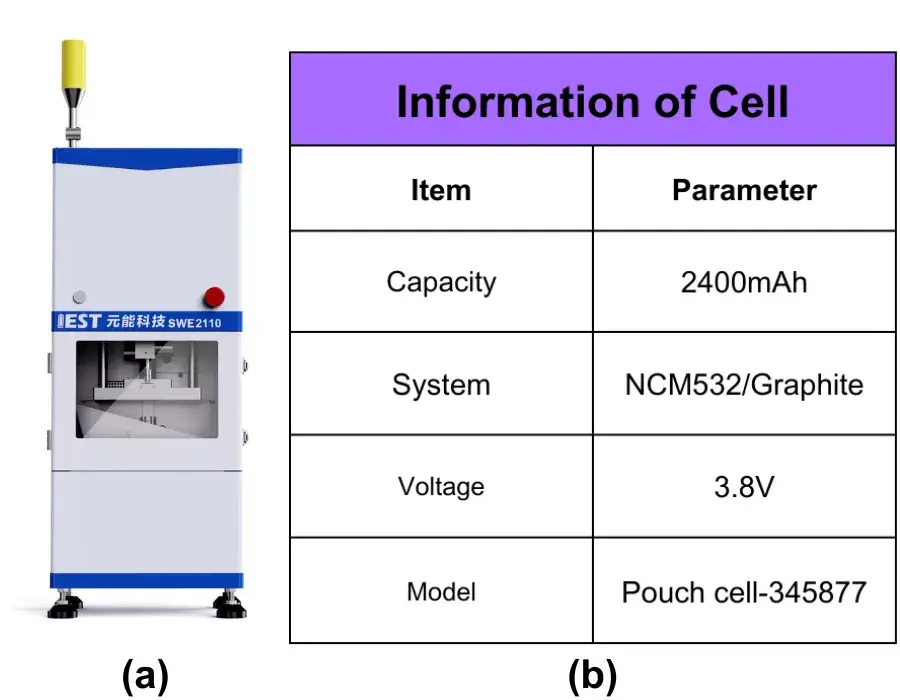

Figure 1. IEST SWE instrument and battery information

We prepared NCM pouch cells at specific SOCs, with parameters listed in Figure 1(b). Cells were charged at 0.5C and discharged at 1C within the analyzer’s temperature-controlled chamber (Figure 1a). Tests were conducted at 25°C, 15°C, 10°C, and 0°C, while the analyzer recorded thickness variation curves under constant 5kg force.

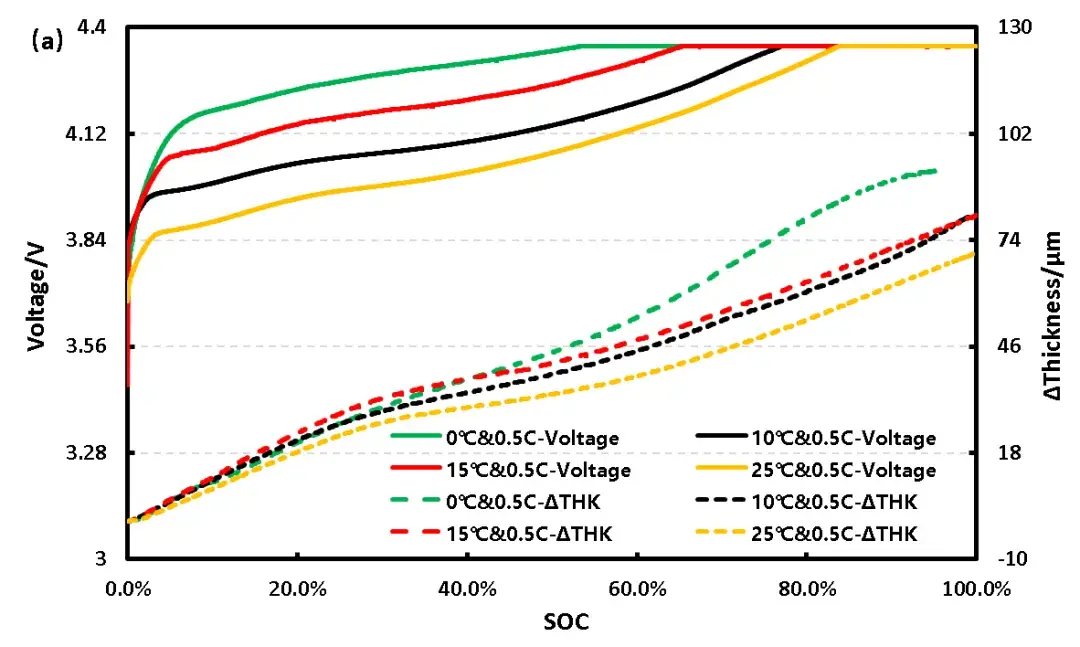

Figure 2(a) shows the charge capacity-SOC-thickness curves for the pouch cell under identical charging rates at the four temperatures. Maximum thickness expansion was 70.6 µm, 80.4 µm, 80.1 µm, and 92.4 µm, corresponding to expansion rates of 2.08%, 2.35%, 2.35%, and 2.71%, respectively. The 0°C curve deviates significantly, particularly in the high SOC region where the slope of the thickness curve differs, suggesting potential lithium plating at 0°C.

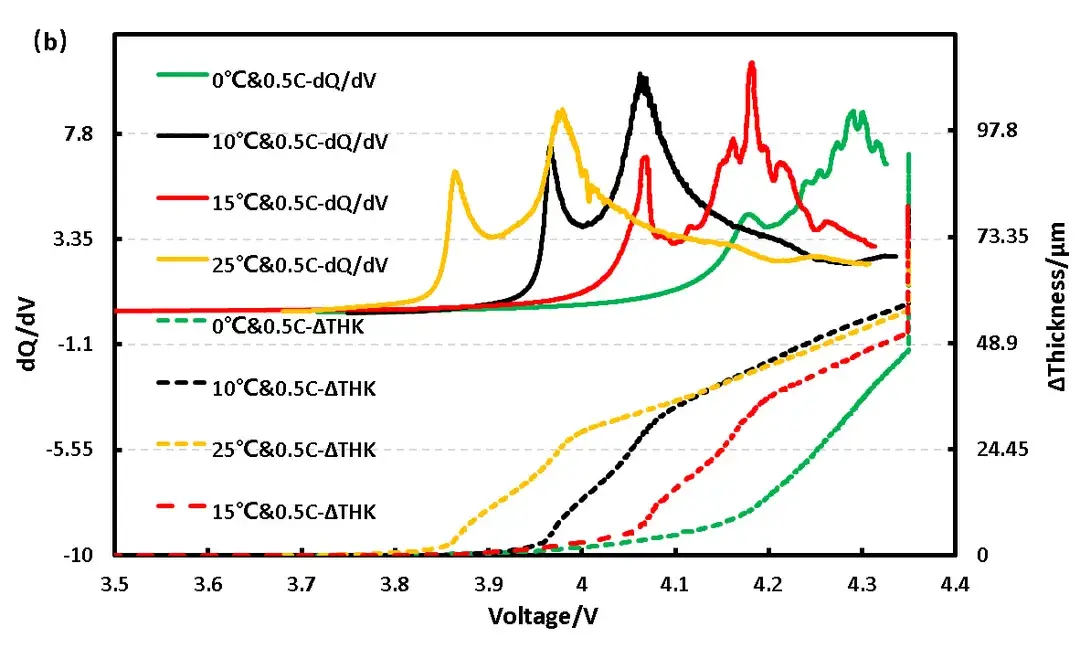

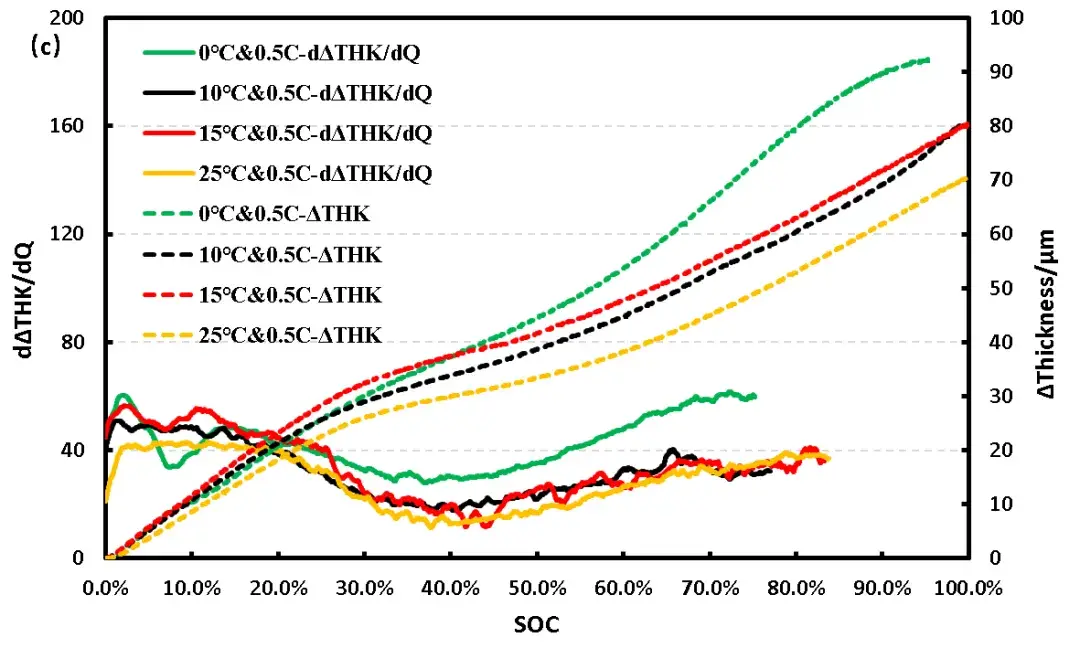

Further analysis of the differential capacity curves (Figure 2b) shows that peaks corresponding to phase transitions during (de)intercalation align with inflection points in the thickness expansion rate. As temperature decreases, these peaks shift rightward, indicating increased polarization. Comparing thickness curves (Figure 2a), the 0°C case shows a pronounced slope change and greater total expansion at that point. The differential thickness curve (Figure 2c) confirms that beyond 30% SOC (approx. 4.27V), the expansion per unit capacity at 0°C exceeds that at higher temperatures, strongly implying lithium plating due to enhanced polarization.

Figure 2. (a) Charge capacity-SOC-thickness curves of pouch cells at different temperatures

Figure 2. (b) Differential capacity-voltage-thickness curves of pouch cell at different temperatures

Figure 2. (c) Differential thickness-SOC-thickness curves of flexible pack cells at different temperatures

5. Multi-physics Modeling of Lithium Dendrite Formation

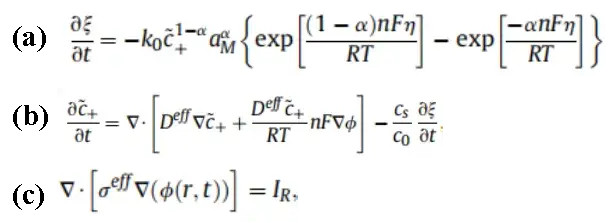

Through the expansion lithium plating experiments, the thickness variation data of the cell cycling at different temperatures were obtained, in which the thickness capacity differential curves indicate the time, capacity and temperature windows corresponding to lithium plating. Then, through further theoretical analysis, an attempt was made to calculate the specific amount of lithium plating under this condition. Battery expansion at different temperatures is a complex multi-physics field coupling problem involving ion concentration field, electric potential field, physical phase field and temperature field. We theoretically analyze the morphology and conditions of lithium dendrite formation by building a continuous thermodynamic phase field model. In the model, three nonlinear equations are usually included:

5.1 Phase field equation

The phase transition of elemental lithium from the ionic to the metallic state with time is proportional to the change in the free energy of the system. Where the free energy of the system can contain the energy generated by the chemical reaction of the battery, the energy of the elastic-plastic change of the material, the thermal energy and so on.

5.2 Ion diffusion equation

i.e., Fick’s second law, the change in solid-phase lithium ion concentration with time is related to the ion concentration gradient along the radius inside the particle. The significance of this equation is that the concentration change in solid phase ion concentration at any given moment is related to its diffusion coefficient and concentration gradient.

5.3 Potential distribution equation

For the electrostatic potential distribution, assuming charge neutrality in the system, the current density is considered to be conserved by Poisson’s equation, including a source term to represent the charges entering or leaving due to electrochemical reactions.

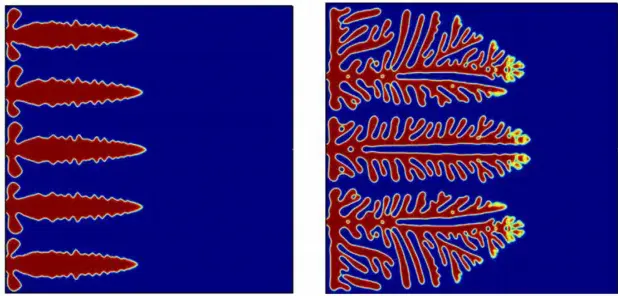

By entering the set of nonlinear equations (a)(b)(c) into Comsol software, the lithium dendrite morphology can be calculated for a specific temperature, multiplicity and voltage. This is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Lithium dendrite simulation results

6. Volume Change: Lithium Plating vs. Graphite Intercalation

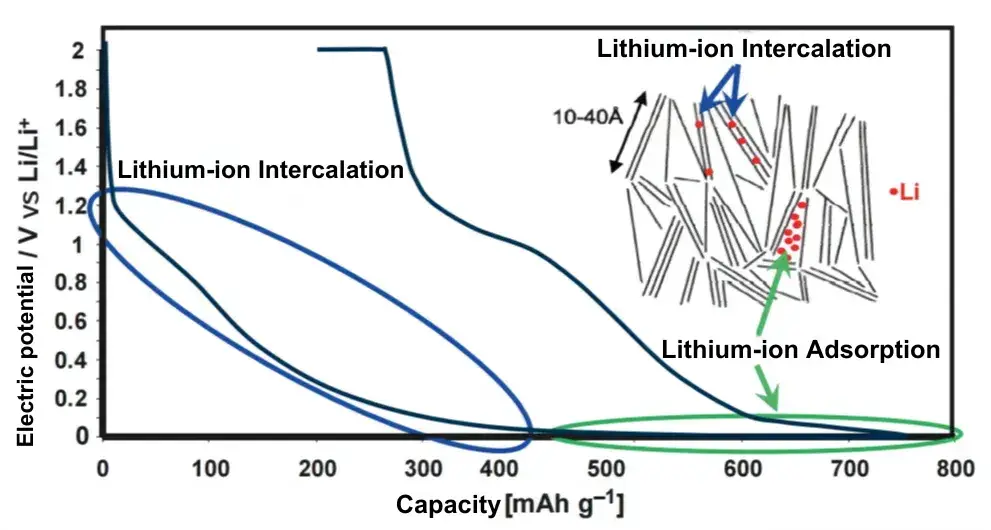

In graphite/ternary batteries, the volume change of anode is very small (≤1%), while the volume change of graphite full embedded lithium state is 10%. Therefore, the volume change of the battery is mainly determined by the graphite anode. Of all the carbon atoms in the graphite material, one ion can be stored for every six carbon atoms, so the maximum amount of lithium ions that can be stored in graphite is one lithium atom for every six carbon atoms, and the minimum amount of lithium ions that can be stored is zero. Therefore, when talking about the degree of lithiation of a graphite electrode, we use the symbol LixC6, where 0 ≤ x ≤ 1. Clearly, at the atomic level, for any C6 ring, either only one lithium atom is inserted in the ring or no lithium atoms are inserted. However, when considering the entire electrode, only a fraction of the C6 rings will have lithium ions embedded in them, and this fraction is the value of x. When the battery is charged, the negative electrode is highly lithiated, and in the lithium-rich state the x in LixC6 is close to 1. When the battery is discharged, there is a large amount of de-embedded lithium atoms in the negative electrode, and in the lithium-poor state the x in LixC6 is close to 0. The lithium-rich state is the same as the lithium-poor state.

The electrochemical insertion reaction of desolvated lithium ions in graphite occurs in the potential range of 0 to 0.25 V vs Li/Li+. The insertion reaction occurs at well-defined voltage plateaus, and there are also well-defined insertion compounds at the beginning and end of the voltage plateaus. Experiments show that the lithium intercalation step is measurable. Hexagonal (ABABAB) and rhombic (ABCABC) graphite structures are transformed into an AAAAAAA stacking sequence with inserted lithium during the lithium embedding process, respectively. The lithium is located in the center of the C6 ring between the two graphene layers. Thus, the capacity of graphite depends on the number of available graphene layers. If a very well structured graphite (e.g. natural graphite) is used, it can be almost fully charged up to a theoretical capacity of 372 mAh/g in a multiplicative charging scenario, and Figure 4 shows the anode changes during the lithium insertion process.

Figure 4. Graphite-embedded lithium potential curves and schematic diagrams

The insertion of lithium ions into the anode lattice fills the free gap, so that the volume of the intercalation compound is less than the sum of the volumes of the two individual materials. The increased thickness of the intercalation material does not cause significant expansion of the battery. However, lithium metal deposited on the surface of the negative electrode significantly increases the thickness of the pouch cell. Transferring a charge of 1Ah from the cathode to the anode, the amount of lithium material is 37.31 mmol. every six carbon atoms provide space for one lithium atom to insert. Therefore, for a charge of 1Ah, 0.2239 mol of carbon is consumed. The volume of this portion of carbon is 1.189 cm³. According to the literature, it is known that the carbon-based anode material expands by about 10% due to the insertion of lithium ions. Therefore, charging 1Ah results in a volume change of 0.12cm³. When lithium ions are reduced to lithium metal precipitated on the surface of the anode, the volume of lithium metal reduced by 1Ah charge is 0.49cm³, assuming dense deposition of lithium. If the lithium forms a dendritic morphology (Figure 3), the precipitated lithium becomes fluffy and the volume increases even more. Assuming that the percentage of lithium dendrites is x%, combined with the morphology of lithium dendrites under this condition, and based on the data measured by the in-situ expansion equipment at the specified constant pressure and the measured Young’s modulus of the cell, the calculations lead to a lithium plating of 4% under the cycling condition of 0°0.5C in Figure 2(b).

7. Summary

The in-situ swelling analyzer developed by IEST can accurately detect the thickness change of batteries under specified working condition cycles. The lithium plating temperature and SOC window under specific conditions can be accurately determined by thickness differentiation and other algorithms, and the amount of lithium ions consumed by lithium dendrites can be roughly calculated by combining with lithium dendrite morphology simulated by comsol, providing valuable insights for battery development and charging strategy optimization.

8. References

[1] B. Bitzer, Gruhle. A new method for detecting lithium plating by measuring the cell thickness. Journal of Power Sources, 262 (2014) 297~302.

[2] Modulation of dendritic patterns during electrodeposition: A nonlinear phase-field model

Contact Us

If you are interested in our products and want to know more details, please leave a message here, we will reply you as soon as we can.